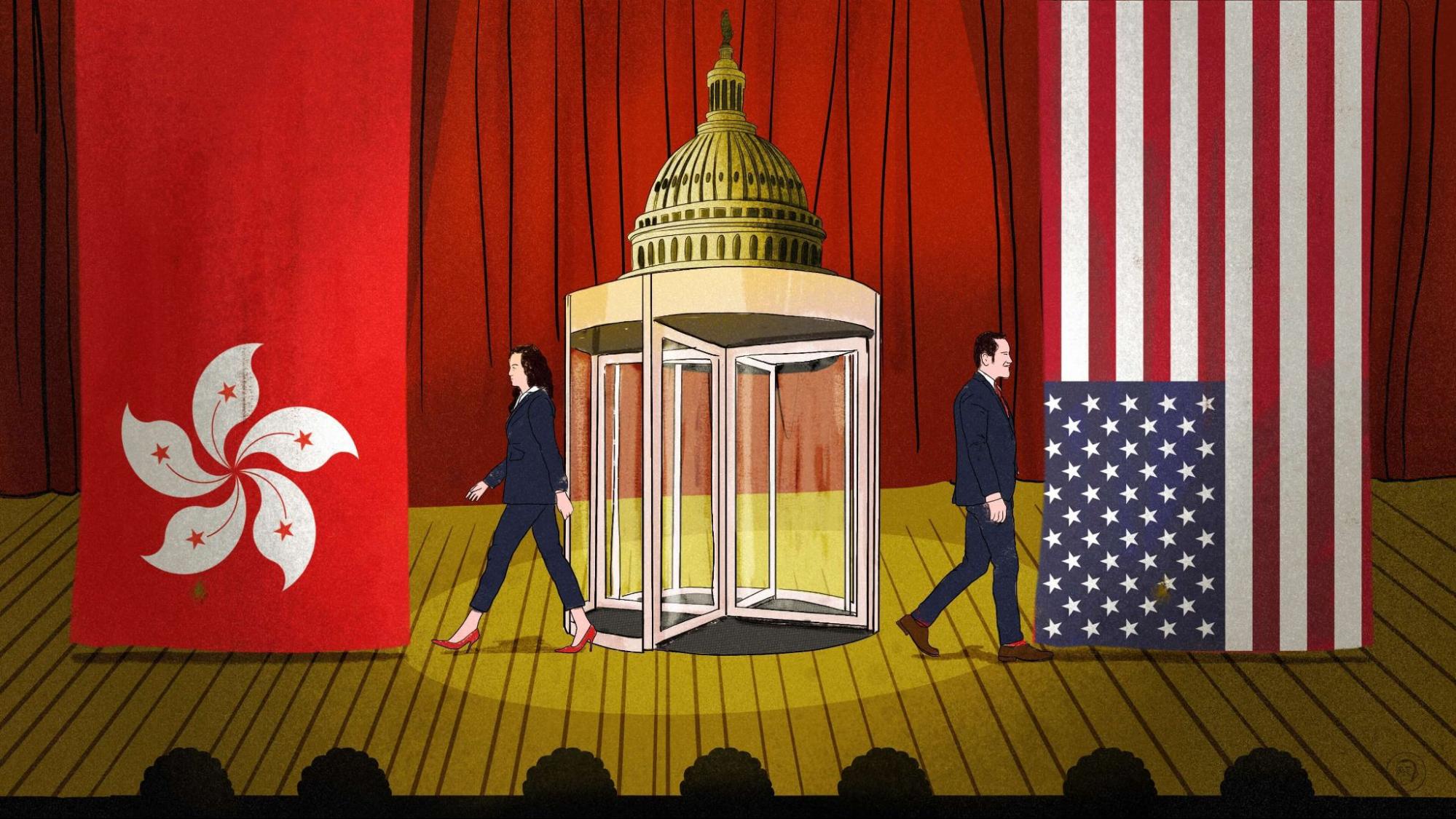

The best-connected people the Hong Kong government can buy are lobbying the U.S. government

A new report from the Hong Kong Democracy Council details Hong Kong government affiliates’ lobbying activities in Washington, and the former Congress members on their payroll. Hong Kong Democracy Council’s Mason Wong told us all about it.

A new report published last Wednesday by the Washington, D.C.-based Hong Kong Democracy Council describes the ways the Beijing-backed government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region exerts influence in the U.S. by lobbying elected officials, hosting business and culture events, and supporting media outlets.

The report and an accompanying database detail the work of Hong Kong government offices and media in shaping public opinion and policy in the U.S. Among the influence activities is lobbying against the 2019 Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, legislation that eventually led to sanctions against Chinese and Hong Kong officials the U.S. deemed responsible for human rights abuses during the city’s anti-extradition protests that year.

I spoke with the author of the report, Mason Wong, to ask about some of the details, and to better understand how the lobbying activity may change going forward. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

— Eduardo Jaramillo

If readers take away one thing from this report, what do you think it should be?

The most important takeaway is that there are well-connected Washington insiders advocating against human rights legislation, on behalf of the Hong Kong government. I think that’s a thing worth noting. [The report] covers a lot of things, but I think this current situation where we have these well-connected former congressmen or former federal government officials doing a hostile foreign government’s bidding, this is just unconscionable.

That’s the whole ball game — if you don’t understand the lobbying, you don’t understand the Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA), it’s very complicated, that’s okay. You should know, there are important Washington insiders doing the Hong Kong government’s bidding here, and it’s to oppose human rights legislation, and to oppose supporting a democratic movement.

Some key players here are the foreign principals that advance Hong Kong interests in the U.S. Can you give a quick sketch of these entities and how they exert influence on behalf of the Hong Kong government?

So I think we should start with HKETO and HKTDC. The HKETOs are the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Offices, established close to their current form in the 1980s during the colonial era. After the handover, they have had a kind of special set of quasi-diplomatic privileges, which are conferred by both Congress and by an executive order signed by Bill Clinton in 1997. So they aren’t FARA-registered foreign principals exactly, or at least they are not the ones who are on the lobbying forms, even though they direct all of the lobbying activities in actuality. They run several offices around the world, including three in the U.S.

And then you have the Hong Kong Trade Development Council, HKTDC, a statutory body of the Hong Kong government, which on paper is mostly here for business promotion, but it provides all the money to pay lobbyists and it is the foreign principal that all of the agents work for. There’s almost a “man behind the man” situation here where HKETO is doing all of the direction, and HKETO officials are the ones accompanying lobbyists to meet members of Congress, but HKTDC is the name that’s put down on the forms, and the contracts are signed between lobbyists and HKTDC.

Sing Tao is a kind of separate issue in that it’s not state media exactly, it’s a company that nonetheless has very strong ties to the Hong Kong government and to the CCP in general, through who owns it and through its media stance. It’s considered to be a pro-government outlet, and because it’s a pro-CCP or pro-SAR government outlet, it has been forced to register as a foreign principal and a foreign agent, sort of like HKTDC has, where it is considered a sort of vector of influence in some manner by the U.S. government.

On the other side of this are the foreign agents, which are often lobbying firms. The key ones you identify in this report are Akin Gump Strauss Hauer & Feld LLP, Venable LLP, and BGR Government Affairs. Who are some of the key high-profile lobbyists, and how do they try to shape narratives about Hong Kong in Washington?

We have on our database the names and biographies of all these different lobbyists and their corresponding FARA filings. At Venable for example, there’s Bart Stupak, a former Democratic congressman from Michigan, who was sort of a minor but important player in the Democratic caucus, important in the negotiations over Obamacare. He was enlisted to really spearhead the lobbying effort against the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act. You can see this is a well-connected guy who was a sort of wheeling-and-dealing character in Congress, who has now turned these skills around to represent a foreign government to lobby against human rights legislation.

Akin Gump is also quite notable. You have, on the other side of the aisle, two former Republican House committee chairs. One is Lamar Smith of Texas, who was an anti-climate-change fixture on Fox News, also very high profile and knows a lot about congressional procedure, and also chaired the Judiciary Committee, and the Ethics Committee. So: a dyed-in-the-wool House insider who is now a foreign agent for the Hong Kong Trade Development Council.

Ileana Ros-Lehtinen is another one, who was a Florida Representative for around 30 years and chair of the House Foreign Relations Committee, whose work for HKTDC I think a number of people found surprising because she was very supportive of different human-rights-related legislation. She actually co-sponsored a bill about determining the scope of Chinese influence operations in the U.S. Lamar Smith has done something similar. He raised concerns about “sleeper agents” stealing American trade secrets. Generally, I think these are people who were actually very anti-China in some way and involved in foreign policy in some capacity, or science and tech policy, who are now on the other side of that interaction.

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

They are really getting elite, well-connected people. They’re not random lawyers or something like that. These are the best-connected people that the Hong Kong government can buy. And so I think that’s a notable thing in the foreign influence discourse, that it’s these types of people doing it.

So they’re committing a lot of resources here — around $35 million in reported FARA spending since 2019, according to your report. But is it working? The efforts to block the passage of the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act failed. Are there notable legislative successes that they can point to?

No, and I think this is interesting, actually. A Hong Kong activist remarked to me that he was shocked to read this report because it looks like they’ve spent about 100 million Hong Kong Dollars to get basically nothing, and by and large, they haven’t been very successful.

I think that the reason we’re concerned about this, even despite the lack of obvious legislative successes, is that there’s not a lot of Hong Kong expertise either on the Hill or in foreign policy circles in general. There’s an increasing number of people who speak Mandarin and follow China, but very few know what’s going on in Hong Kong: We don’t have enough people who speak Cantonese, who know the political environment, all the parties, the government, things like that.

And so we’re worried that congressional offices or state governments will be meeting these lobbyists and getting information from them on trade issues. As these things become more relevant, like with Hong Kong’s role in the export controls debate, we’ve noticed an uptick in the hiring of trade-related lobbyists and trade lawyers and also their meeting with state-level governments. Hong Kong activists don’t necessarily have the resources to be in every single state talking to every governor. So we’re seeing that they’re filling out a gap in knowledge, and we find that concerning.

The report talks a lot about attempts to influence public opinion. That’s partly through media like Sing Tao, but there are also cultural events at museums and other venues. Can you talk a bit about that and whether you see any evidence that these activities cut through and actually influence American public opinion?

Yeah, I would say the cultural partnerships piece is very interesting because it’s part of what we would consider to be a more low-key propaganda effort. We tend to think of propaganda as things like Xinjiang genocide denialism, or Chinese propaganda related to military affairs, or the lab leak stuff about Fort Detrick being where the coronavirus came from.

In Hong Kong, it’s a little different because what they’re trying to do is not to attack the United States necessarily, but to convince the world that Hong Kong is a normal and safe place to live, especially for foreigners. And so we see this as continuous with things like the “Hello Hong Kong” campaign to get foreigners to go to Hong Kong, to get them free plane tickets, expedited visas, things like that. At different events, HKETO officials will say that Hong Kong has a robust legal system, it’s a safe place to do business, there’s transparent and accountable government services, it has an independent judiciary.

Regarding HKETO’s partnerships with museums and art galleries, something that we’ve heard from a lot of Hongkongers and the arts community, especially people who’ve been involved in the protests, was that there’s a very clear selection of either non-political or even anti-political content, just to paper over the fact that there is a huge amount of what you would call dissident art or protest art. I would compare it to another government trying to just not talk about a war that’s being fought, or even in certain states in the U.S. when politicians try openly not to discuss certain social issues. So that’s one of the major issues we see.

Another big part of this report is about the Hong Kong Economic and Trade Office Certification Act, which will potentially end HKETO’s U.S. operations. Is this legislation likely to pass and be signed into law?

I think we’re hopeful — that’s all I’ll say at this time, I think we’re hopeful that we can get moving on this legislation. I do think this is a good piece of legislation in terms of its varied methods for oversight of the HKETOs: Obviously there’s presidential review of the HKETOs’ special legal status, but also congressional review of what the president decides as well.