Cultural boon or abomination? American-Chinese food arrives in Beijing

While homesick expatriates and locals who have studied abroad welcome the restaurant with open arms, others say they will only try its food once out of pure curiosity.

Chop suey. Egg foo young. Crab rangoon. And, of course, sesame orange chicken.

For a lot of Americans, these dishes have functioned as an introduction to Chinese food — albeit a very Americanized version. Anyone with a passing knowledge of Chinese cuisine would know that foods like General Tso’s chicken aren’t a thing in authentic Chinese cooking. Or, in other words, most Chinese people have never heard of them, and they were for a long time impossible to come by in Beijing.

But that’s no longer the case. In May, Bamboo Chinese Fast Food (竹子快餐 zhúzi kuàicān), an establishment specializing in American-Chinese dishes, opened in the Chinese capital. In the past few weeks, the establishment has gained traction on Chinese social media, spurring intrigue from local Chinese who are unfamiliar with the cuisine and positive reviews from nostalgic expatriates and those who have studied abroad.

Tucked inside a slightly dingy-looking food court in Beijing’s Liangmaqiao area not too far from the U.S. embassy, the restaurant is an unassuming hole-in-the-wall with a greasy, get-down-and-dirty vibe that one would expect from a typical Chinese takeout in the U.S.

Tiny, inexpensive, and with both counter service and delivery, the spot serves up a small menu of staples in American-Chinese cuisine, including beef and broccoli, honey walnut shrimp, chow mein (fried noodles), and fried rice, with prices ranging from 16 yuan ($2.20) to 52 yuan ($7.20).

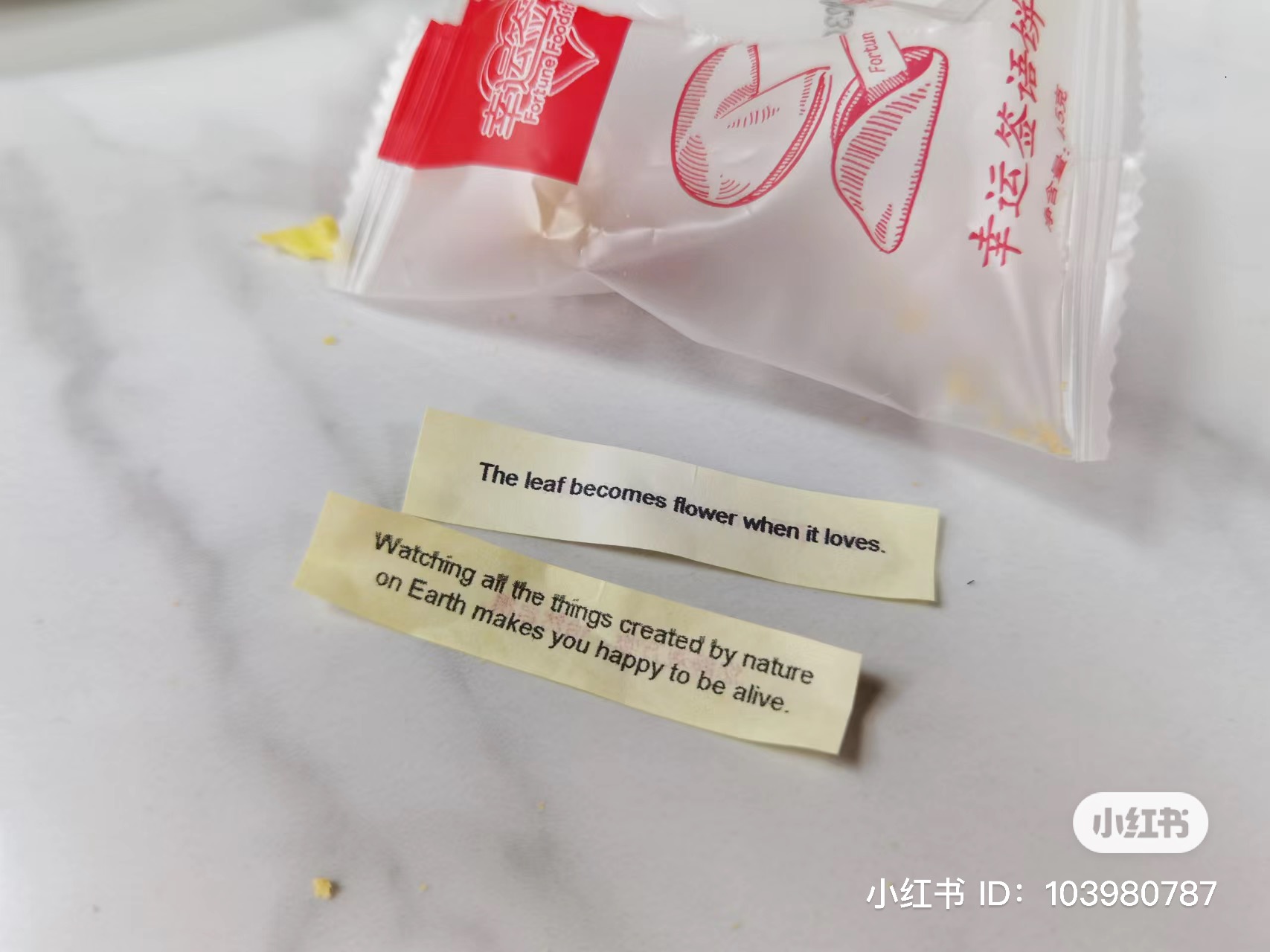

And just like a classic rundown Chinese restaurant in an American suburb, Bamboo Chinese Fast Food uses the famous white cardboard takeout boxes and gives out fortune cookies to customers.

In an article published this week by Real Story Research Lab (真故研究室 zhēn gù yánjiūshì), a popular public WeChat account profiling ordinary Chinese people, the owner of the shop, who calls himself Tank (坦克 tǎnkè), confessed that although he had never lived in the U.S., he first encountered American-Chinese food on a trip to the country when he was little. “The sweet and sour flavor left a good impression on him,” the author wrote.

According to the profile, because it’s difficult to find chefs in Beijing who had experience making American-Chinese dishes, Tank worked on recipes by himself before launching the restaurant. In order to cater to the Chinese palette, he also adjusted flavors of the food, making them not “overly sweet or sour” for locals.

One of the interesting anecdotes from the profile is that Tank’s mom, who actually resided in California for some time, was critical about his business proposal. She told the publication, “I don’t go to those Chinese takeouts when I’m abroad. Why would I want that kind of food in China?”

Not everyone feels this way. Judging from reviews of the restaurant on Chinese social media, its core demographic right now includes expatriates living in Beijing and locals who got hooked on “inauthentic” Chinese food when studying overseas. In a Bilibili video posted in June that has racked up more than 160,000 views, a pair of young Beijing residents visited the restaurant and tried every item on the menu. “I had real American-Chinese food before when I spent some time in the U.S. as a college student. I’ll decide if the food here is authentic or not,” one of them said, before gobbling down plates of food doused in orange sauce and leaving a positive review.

Under posts about the restaurant on Xiaohongshu, many compared the dishes at Bamboo Chinese Fast Food to those served at Panda Express and P.F. Chang’s, saying that although they were initially reluctant to try Westernized Chinese food when studying or working aboard, they eventually came around and even started craving it after they returned to China.

“Before I came back to China, I thought I would never want to have this type of food again. Now, I have to admit that I kind of miss that strange sweet and sour smell,” one commented. Another person wrote, “Color me interested! I unironically love Panda Express.”

While some expressed disdain for the restaurant, with one describing it as “reverse cultural shock” and another calling its patrons “victims of Stockholm syndrome,” others applauded Tank’s venture from a business point of view. “It’s not for everyone, but there’s a customer base for it given how many Chinese students return from abroad every year,” one noted.

American-Chinese cuisine can be traced back to the 19th century, when Chinese immigrants first arrived in America during the California Gold Rush and a slew of Chinese food establishments, then referred to as “chow chow houses,” sprang up in San Francisco to feed the population. Because Asian ingredients weren’t easily available back then, Chinese cooks at the time had to work with what they had and put their own spin on Chinese cuisine. As time went on, the dishes served at Chinese restaurants in the U.S. changed even more once they started serving to a white American audience.

By 1989, Chinese food had become the most frequently consumed among 19 different cuisines in the U.S., according to a survey by the National Restaurant Association. Although chain eateries making American-style Chinese food — namely, Panda Express — have faced their own share of complaints about inauthenticity and cultural appropriation over the years, they have also been many Americans’ first introduction to Chinese cuisine, while popularizing dishes like General Tso’s chicken (which Bamboo Chinese Fast Food mistakenly calls “General chicken”).

Bamboo Chinese Fast Food wasn’t the first China-based business trying to introduce the American version of Chinese cuisine, but previous attempts have been unsuccessful. In 2014, two American expatriates, Fung Lam and Dave Rossi, opened Fortune Cookie, Shanghai’s first American-Chinese restaurant, which offered an array of mainstays in American-Chinese cuisine, including kung pao chicken and sesame shrimp. The establishment was a hit in the beginning — with Chinese customers reportedly asking for their food to be served “in American-style white cardboard takeaway containers, mimicking meals they’ve seen on sitcoms like Friends and The Big Bang Theory,” as BBC reported. But it closed two years later, as its novelty faded.

It’s a tough feat to pull off even for large companies with seemingly endless resources and more sophisticated market research. In 2018, American-Chinese chain P.F. Chang’s, which calls Arizona home and has more than 200 locations worldwide, made its first foray into China with a restaurant situated in a high-end mall in Shanghai. “Our food is a perfect fit with the Chinese palette and the way China is headed,” Michael Osanloo, the then CEO of P.F. Chang’s, told NBC News in the wake of the restaurant’s opening. Noting that about 70% of its patrons were local, Osanloo told the publication that the chain hoped to launch at least 10 more locations in Shanghai in the coming years.

In less than a year, P.F. Chang’s shuttered its outpost in Shanghai. Meanwhile, its main competitor, Panda Express, has opened locations in multiple Asian countries, including Japan and South Korea, but not China.