The Saudi-Iran deal: China’s first geopolitical moonwalk

The Chinese-mediated détente between Saudi Arabia and Iran represents a significant milestone in China's global footprint and strategic competition with the United States. At the same time, it underscores why both superpowers' contributions are needed to maintain regional peace and stability.

Fifty-some years ago, the world was awestruck as the United States made history by landing the first man on the moon. On March 17, the world was in awe again, this time as China brokered a normalization agreement between archrivals Saudi Arabia and Iran in Beijing. As aptly described by a prominent Chinese scholar, “one small step for Saudi-Iranian relations, one giant leap for peace and stability in the Middle East.”

The historical reference is particularly fitting when considering the heavily politicized circumstances. The space race represented a way for America and the Soviet Union to demonstrate their technological superiority during the Cold War. In today’s great power competition, the Beijing breakthrough was an opportunity for China to demonstrate its diplomatic prowess over its strategic competitor.

To be sure, Beijing pushed at an open door by acting as a platform for conflicting parties who had long sought a truce. Nor has China made any stated security commitments or assurances in the event that one of the parties violates the accord. But this should not ignore the fact that Beijing was able to forge ahead in uncharted territory; never before had it led a mediation process, let alone successfully. Whereas in the past, China was content to support opposing parties from the sidelines and follow agendas set by Washington, this time around, America was not even in the room.

Just as the moon landing necessitated meticulous planning, attention to detail, and a willingness to take risks, brokering peace between two bitter adversaries entailed China navigating complex geopolitical and cultural landscapes. At the same time, both historical events only mark the beginning of “human exploration,” as Sun Degang of Fudan University noted. It is “only the first step in a long march.” Sectarian and religious divisions, deep mistrust, proxy wars, and a plethora of competing domestic, non-state, regional, and extra-regional actors stand between a Chinese version of Apollo 11 and a space-shuttle disaster.

As a final point of comparison, do you remember Michael Collins? He was the third astronaut on the Apollo 11 mission, and operated the command module orbiting the moon while his crewmates Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin took all the credit on the lunar surface. Multiple other actors in this diplomatic breakthrough played a role similar to Collins’s — somewhat overshadowed, but critical supportive roles in the negotiation’s success.

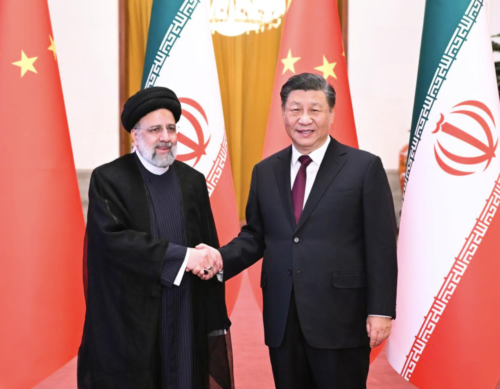

A beaming Wáng Yì 王毅, China’s top diplomat, was able to secure the photo finish with the Iranian and Saudi representatives, prompting comparisons by Chinese observers to the U.S.-led Camp David and the Oslo Accords. The gossamer deal, in fact, sent the entire Chinese party-state propaganda apparatus and diplomats into overdrive, all hailing it as a solid example of Xí Jìnpíng’s 习近平 Global Security Initiative (GSI) in action. They believe it not only demonstrates the great political sagacity of Xi — who had just been coronated for a third term as state and military leader — but also that the “Beijing Consensus” offers a superior alternative to the U.S.-led West’s system of global governance.

Yet, Collins’s humility reminds us that China’s success would not have been possible without two years of hard work by the opposing parties, Iraq, Oman, and even the United States. Yes, the same United States that the party-state now relentlessly blames for all the problems in the Middle East.

The reason why China now wields so much leverage over Iran and Saudi Arabia is it has been able to operate freely, secure nearly half of its energy imports, and thrive in the Gulf under the American security umbrella. Without the “U.S.-led West’s” blood and treasure, there would have been no peaceful and stable foundation for Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative and its vast network of infrastructure and Silk Roads in the region. The Ayatollahs’ regime may not have even shown up at the negotiating table without the American “maximum pressure” campaign.

The White House should, and has, recognized Beijing’s contribution. As of the time of writing, four U.S. officials, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, have responded positively to Beijing’s mediation, saying that anything that helps to cool the flames in the Gulf is in America’s best interests. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan has even candidly acknowledged that given the nature of Washington’s relations with Tehran, the U.S. was never in a position to serve as a mediator.

China should take a cue from these remarks and accept its own power limits. The same Chinese analysts who have triumphantly criticized America’s failed Middle East policy since last week’s events have until recently admitted that their country lacks understanding and trust in the region. They agree that the recent development has not changed China’s more cautious approach to international security and diplomacy, nor its stated commitment to refrain from acting as the “world’s police” by interfering in the internal affairs of others. Beijing’s mediation efforts haven’t been able to resolve all of the region’s security problems, particularly Iran’s financing and support of terrorists, proxies, and religious extremists, as well as its nuclear proliferation.

To conclude, Beijing’s first successful “moon landing” ushers in a new chapter in Chinese diplomacy, ratcheting up the geopolitical “space race” with the West. Although balloon-gate demonstrates how acrimonious the great power rivalry has become, it is also a reminder that the two still have overlapping interests. Maintaining peace and stability in the Middle East is but one example.

Rather than using their successes as ammunition to assault one another, Beijing and Washington must accept that maintaining the balance under this “new paradigm” will necessitate both of their contributions. Even though it would be naïve to hope for joint missions to Mars any time soon, the very least they can do for the benefit of a combustible region — and the entire world — is to keep their satellites from crashing into each other.