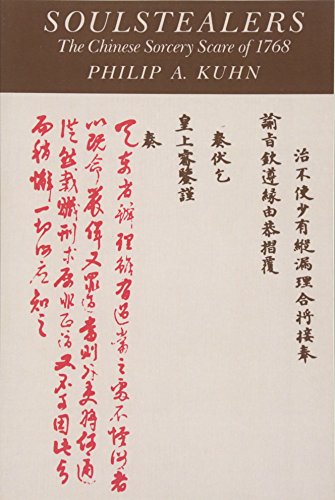

This is book No. 23 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“A masterful study by one of the West’s premier Chinese historians.”

—Frederic Wakeman, Jr., New York Review of Books

“Kuhn’s fascinating particulars demonstrate how in any society provincial panic can become a national witch-hunt.”

—New Yorker

“A subtle, powerful, and still relevant inquiry into the dynamics of autocratic rule.”

—From the Joseph Levenson Book Prize citation

“Kuhn’s depiction of the numerous grievous weak spots of the legal system and government is detailed and convincing; the friction between the lower Yangtze River culture and the culture of the rulers in Beijing that he reports resonates in modern China.”

—The Boston Globe

About the author:

Philip A. Kuhn (1933-2016) was a highly regarded American Sinologist at Harvard University. Kuhn was born in London, where his father was bureau chief for the New York Times. He studied at Harvard and then studied Japanese and Japanese history at SOAS back in London. He served in the U.S. Army for several years in the 1950s, where he studied Chinese and Chinese characters at the Defense Language Institute in California. Kuhn’s Ph.D. supervisor and mentor at Harvard was John K. Fairbank.

Kuhn wrote extensively on the Taiping Rebellion and published Rebellion and Its Enemies in Late Imperial China: Militarization and Social Structure, 1796-1864 in 1970, described as a “landmark study.” Soulstealers (1990) was his second book, which Jonathan Spence (see book No. 15) praised for drawing attention to the often-neglected role of shamanism. Kuhn also wrote the highly influential Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times (2008), a comprehensive study of the Chinese diaspora.

The book in 150 words:

Midway through the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, Hónglì 弘曆, in the most prosperous period of China’s last imperial dynasty, a mass hysteria broke out among the people. They feared that sorcerers were clipping off the ends of men’s queues (the braids worn by imperial law), chanting magical incantations, and stealing their souls. Kuhn’s book examines this epidemic of fear and the official prosecution of the supposed “soulstealers” that ensued.

Kuhn’s phenomenally impressive research involved investigating documents found in the imperial archives recounting the questioning and persecution of various vagabonds, beggars, and religious figures. Kuhn shows how the campaign against sorcery provides insight into the period’s social structure and ethnic tensions, the relationship between monarch and bureaucrat, and the inner workings of the Qing state. And, crucially, how the suppression campaign offered Hongli a chance to force provincial chiefs to crack down on local officials and restore top-down order.

Your free takeaways:

In the year 1768, on the eve of China’s tragic modern age, there ran through her society a premonitory shiver: a vision of sorcerers roaming the land, stealing souls. By enchanting either the written name of the victim or a piece of his hair or clothing, the sorcerer would cause him to sicken and die. He would then use the stolen soul-force for his own purposes.

Yet fear of sorcery remained deeply embedded in the public mind. Was there no protection against this scourge? How little the public had been reassured? By June 21 the panic had broken out of the lower Yangtze provinces and had spread five hundred miles upriver to the prefectural city of Hanyang: there a large crowd at a street opera seized a suspected soulstealer, beat him to death, and burned his corpse.

Sorcery panic struck China’s last imperial dynasty, not during its waning days, but at the height of its celebrated “Prosperous Age.” Sorcery’s dread image was refracted through every social stratum.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

We speak so often now about the layers of the contemporary party-state, from the top leaders in Zhongnanhai down to provincial, local, town, municipality, and eventually village officials and cadres. In part of course this is an integral component of the Communist Party’s state machinery — orders can move and down the chain and at various points the lower levels can choose to ignore or slightly alter their orders (“the mountains are high and the emperor far away”), and, of course, vice versa, as the leadership distances itself from local decision-making when it proves unpopular. We also still see attempts to deal with both organized and unorganized religion and belief systems in China, be it Islam in Xinjiang, Buddhism in Tibet, underground Christian churches, or phenomena such as the Falun Gong. Philip Kuhn’s Soulstealers shows us this process has been going on for centuries and across dynasties and republics. According to Kuhn, the targeting of Buddhist monks during the panic in 1768 was probably linked to common beliefs that attributed religious figures of Buddhism or Taoism with mystical, supernatural powers.

Of course, Kuhn’s study adds to our understanding of “witch hunts” — from Salem to McCarthyism, from the persecutions of the Cultural Revolution to that of Falun Gong practitioners in modern times. Kuhn is clear that, according to the archives, torture was used to extract confessions. Soulstealers also has other contemporary resonances with how different levels and parts of the government apparatus see events such as uprisings, alternative power structures (e.g., churches), etc. In 1867, local officials saw the problem as largely due to troublemaking bandits and occasionally blamed the “sorcery” on foreign churches for personal gain. However, more senior Manchu officials far away from the center of events in eastern China and closer to the imperial court in Beijing saw the series of events more worryingly as an attempt at insurrection.

While Soulstealers shows us the long-running uses and abuses of traditional beliefs, superstitions, and mythology (as well as the fact that China can suffer from various mass formation psychosis), it is also an important work in showing just how earlier periods of Chinese history can be unearthed and understood through the extensive archives, including confessions, trial records, court letters, secret (and not-so-secret) memorials, and, amazingly, the vermillion rescripts of the emperor and the local law codes. Other historians have managed to dig deep into archives, though Kuhn’s Soulstealers perhaps remains the gold standard of Qing dynasty archival research.

And Soulstealers still echoes down the centuries to us. As one reviewer, HL Kahn, in the Association for Asian Studies journal, wrote, in the case of 1867 “autocratic power floundered before routine. The sovereign’s salvation was the political campaign — in this case against ‘political crime’ — a concept which some may find modern.”

Next time:

In many ways, it was not surprising that the Qing administration should see the reports of “sorcery” as attempts at insurrection — this panic was of course merely a few years after the Taiping Rebellion, the massive 15-year civil war in China between the Qing dynasty and the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, commanded by a man who considered himself a brother of Jesus Christ. It is a conflict that left millions dead but also at times controlled land occupied by more than 30 million people. No wonder it is studied and thought about closely by those leading China today as a cautionary tale, even if it’s often under-appreciated in the West, even among veteran China watchers. And so we too must revisit the Taiping.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.