This is book No. 22 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“Mr. Werner thinks that the stimulus of danger, competition of adventure, in their surroundings is necessary to provoke the myth-making qualities in a race, and that the comparative absence of these conditions explains why the Chinese have produced no ‘great’ myths. Nor have they produced great dramas; but Chinese lyric poetry is full of charm, and there is something exhilarating in the world of gods, genii, demons, sages, and fairies who people Chinese myth.”

—The Guardian, March 1, 1923

“The only book of Chinese mythology…it deals only with those myths which live in the middle of the minds of the people and are referred to most in their literature.”

—The Berkshire Eagle

“ETC Werner is an Englishman whose fame has spread far beyond his quiet home here. His Descriptive Sociology of the Chinese is a classic, as is also his Myths and Legends of China.”

—Intelligencer Journal (Pennsylvania)

About the author:

Edward Theodore Chalmers Werner (1864–1954) was a British diplomat-scholar born on a passenger liner arriving at Port Chalmers, New Zealand (hence his middle name). He studied at Tonbridge School and then obtained a Far Eastern Cadetship (a fast-track program at the time for diplomatic service in China). He was stationed at a wide range of locations, including Fuzhou, Shanghai, Hankou (part of modern-day Wuhan), Hangzhou, Hainan Island, Beihai, Jiujiang, Tianjin, Macao, and, largely, Beijing. His career was cut short at the outbreak of the First World War.

Werner was a notoriously abrasive character, but it was the fact that his father was Prussian and his mother English that caused problems. He remained in Beijing after retirement, where he concentrated on his scholarly work. He was also a member of the planning committee for the Peking Union Medical College, a member of the Chinese government’s Historiography Bureau, and on the board of the Royal Asiatic Society China.

Werner published the critically acclaimed (not least by Bertrand Russell) China of the Chinese in 1919 and his best-known work, Myths and Legends of China, in 1922. He went on to write several more books, some well-regarded papers for the Royal Asiatic Society (including a study on ancient Chinese weapons that is still seen as a major work on the subject), and a partial autobiography, Autumn Leaves. A highly accomplished linguist, Werner apparently spoke seven Chinese dialects as well as English, German, Portuguese, Italian, French, Latin, and Mongolian. Werner also had an adopted daughter, Pamela, who was violently murdered in Beijing in 1937. The murder is the subject of a New York Times best-selling book, of which we’ll say no more here!

The book in 150 words:

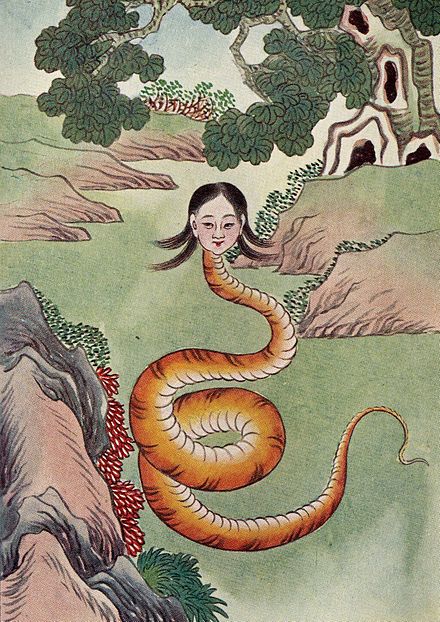

A lengthy study of Chinese myths and legends, with 30 color plates of Chinese gods and mythical creatures. The book begins with a sociological study of China and the Chinese people, which, though now outdated, is revealing of the state of Sinology in the early 1920s. Werner runs through most of the well-known and somewhat obscure legends, placing them in time, region, and context, linking myths and legends to religion, superstition, and the intergenerational transfer of knowledge. Werner’s Myths and Legends of China is not perhaps the most scintillating read on the Ultimate China Bookshelf, but is (despite its age) still a useful directory.

Your free takeaways:

My aim, after summarizing the sociology of the Chinese as a prerequisite to the understanding of their ideas and sentiments, and dealing as fully as possible, consistently with limitations of space (limitations which have necessitated the presentation of a very large and intricate topic in a highly compressed form), with the philosophy of the subject, has been to set forth in English dress those myths which may be regarded as the accredited representatives of Chinese mythology — those which live in the minds of the people and are referred to most frequently in their literature, not those which are merely diverting without being typical or instructive — in short, a true, not a distorted image.

This is, so far as I know, the only monograph on Chinese mythology in any non-Chinese language. Nor do the native works include any scientific analysis or philosophical treatment of their myths.

And we see also that myths may, and very frequently do, have a character quite different from that of the nation to which they appertain, for environment plays a most important part both in their inception and subsequent growth.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Some years ago I visited Lín Yǔtáng’s 林语堂 former house near Yangmingshan in Taipei, which is now a museum to the man and his work (see book No. 20). It’s where he was buried, overlooking Yangmingshan. The museum includes his old rooms, kept pretty much as they were, along with calligraphy done by Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石 Jiǎng Jièshí) and pictures drawn by Madame Chiang (Soong Mei-ling [宋美齡 Sòng Měilíng]). Also, there are examples of his Chinese typewriter, his handwriting in both English and Chinese, and many other mementos of his life, including much of his personal library in multiple languages. And there, prominently on the bookshelf (which should be an inspiration for anyone seeking the ultimate China bookshelf), is ETC Werner’s 1922 classic, Myths and Legends of China.

Lin often told stories of myths and legends in his own books to explain various peculiarities of Chinese life and society — obviously Werner was his source for many of them. Chiang Yee, the artist and writer of the “Silent Traveler” books, also notes that he regularly reached for his copy of Werner’s Myths and Legends when explaining Chinese gods to foreigners in his books, sketches, and paintings.

Werner, a lifelong scholar of China, also had his sources alongside his own large private library — a extensive private library of Chinese manuscripts acquired (and later sold) by The Times journalist GE Morrison (“Morrison of Peking”) — where he held discussions with Herbert Giles, the British diplomat and Sinologist who was the professor of Chinese at the University of Cambridge for 35 years, and the Chinese scholar Mu Hsueh-hsun. He spent hours pouring over the Siku Quanshu (over 3,461 manuscripts compiled by thousands of scholars across China between 1772 and 1781, covering a vast variety of subjects) at libraries in Beijing.

Werner’s Myths and Legends was, when published in 1922, the only authoritative source on the subject in a non-Chinese language. While some earlier passages in the book relating to Chinese history and social character appear dated, they do offer an insight into the state of Sinology and how Western scholars approached China and the Chinese at the start of the 20th century. Werner was much liked in China by scholars and the government, even if some among the foreign community considered him a little too pro-China and to have, in the vulgar phrase of the time, “gone native,” having left the British Foreign Office and diplomatic corps to concentrate on his scholarly work and retired to Beijing rather than returning to England.

Werner was also a great advocate of the theory of sociology espoused by Herbert Spencer in the 19th century — notions of survival of the fittest and that, according to Spencer, a society grows through economic and other acts of spontaneous cooperation by gregarious and social individuals, who are themselves displaying what is called a “social self-consciousness.” Werner is perhaps the most prominent Sinologist to apply Spencerist sociology to Sinology, and does so throughout his lengthy opening chapter, “The Sociology of the Chinese.”

And there is another reason why we look at myths and legends so closely in China. Myths can be something that is used by oppressed people to keep hope alive. Even modern myths and legends can be appropriated — think the use of the Hunger Games motifs in Hong Kong during recent protests. Hence a certain nervousness in modern China over myths, legends, and ultimately history itself from the Taiping to the Falun Gong, vaccine hesitancy to traditional medicine.

Although 100 years old now, Werner’s Myths and Legends of China (available at Project Gutenberg) remains perhaps the most thorough work on the subject, and has been reprinted multiple times. It remains for many one of those books that stays close at hand, constantly picked up to check names, terms, and details.

Next time:

From an overarching study of myth and legend, superstition, and popular beliefs in China, let’s take a close look at one particular episode of the power of myth. Midway through the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, a case of mass hysteria broke out. People feared that sorcerers were roaming the land, clipping off the ends of men’s queues, and chanting magical incantations over them in order to steal the souls of their owners. One book brilliantly re-created this mass hysteria and the myths and legends behind it.

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.