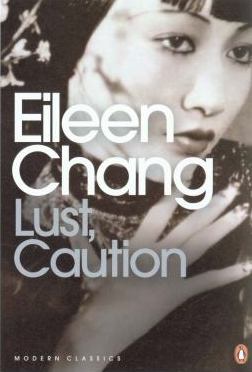

This is book No. 19 in Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.

Blurbs:

“A spy thriller set against the backdrop of socialites and intrigue in 1940s Shanghai and somewhat infamously adapted on film by Ang Lee in 2007, Lust, Caution features Chang’s signature ability to convey simple yet intricate details of her characters’ psychology.”

—Asia Society

“Chang’s sensual writing has elements of both China and the United States; the smoky, formal world of respect for tradition and the irresistible, harshly lighted future.”

—Los Angeles Times

“A master of the short story…Chang’s world is a stark and mysterious place where people strive to find their way in love but often fail under the pressures of family, tradition, and reputation.”

—The New Yorker

“Chang has strong and sensuous power of description…Her stories could hardly be more eloquent.”

—New York Review of Books

About the author:

Eileen Chang (张爱玲 Zhāng Àilíng, 1920-1995) was a novelist, essayist, and screenwriter, born into an elite family in Shanghai. Chang went to Hong Kong to study English literature. In 1941, she returned to Shanghai while the city was under Japanese occupation, and began to work as a freelance journalist writing about fashion and reviewing films. She also began to publish short stories and essays that established her reputation in the literary world. She was in a rather privileged position in Shanghai during wartime, as her partner and then first husband was Hú Lánchéng 胡兰成, a member of Wāng Jīngwèi’s 汪精卫 pro-Japanese collaborationist government.

Chang left China in 1952, unable to find an accommodation with the Communists, and settled in the United States in 1955. She continued to write stories, essays, and screenplays for Hong Kong films. Her career received a major boost in the 1970s when she became popular throughout the Chinese-speaking world, but despite her growing fame, she grew more and more reclusive. She died in her Los Angeles apartment in 1995.

Chang’s works continue to be translated into English, ensuring her international reputation, while the film adaptation of her novella Lust, Caution, directed by Ang Lee, was released in 2007. Hong Kong director Ann Hui has filmed three of Chang’s books — Love in a Fallen City, Eighteen Springs, and, most recently, Love After Love.

The book in 150 words:

Set in Hong Kong and Shanghai during World War Two amid the milieu of the Wang Jingwei puppet government and the Free China resistance, Lust, Caution reportedly took Chang more than two decades to complete. The title is a pun. The character for “lust” (色 sè) can be read as “color,” while “caution” (戒 jiè) can be read as “ring,” so the title can also read as “colorful ring,” an object that plays a crucial role in the story. Wong Chia Chi, a young student active in the resistance, and Mr. Yee, a powerful political figure who works for the Japanese occupational government, engage in espionage and a love affair in Shanghai that is both erotic and ultimately doomed to tragedy.

Your free takeaways:

Though it was still daylight, the hot lamp was shining full beam over the mah-jong table. Diamond rings flashed under its glare as the wearers clacked and reshuffled their tiles. The tablecloth, tied down over the table legs, stretched out into a sleek plain of blinding white. The harsh artificial light silhouetted to full advantage the generous curve of Jiazhi’s bosom…

Apartments were a popular parting gift to discarded mistresses of Wang Jingwei’s ministers. He had too many temptations jostling before him; far too many for any one moment. And if one of them weren’t kept constantly in view, it would slip to the back, and then out of his mind. No: he had to be nailed — even if she kept his nose buried between her breasts to do it.

The people of Shanghai have been distilled out of Chinese tradition by the pressures of modern life; they are a deformed mix of old and new. Though the result may not be healthy, there is a curious wisdom to it.

Why this book should be on your China bookshelf:

Well, the people have spoken — we opened this entry to nominations, seeking to find the book that best defined Chang’s oeuvre (a choice that included one novel, six novellas, and eight short stories), and the finalists were: Lust, Caution, Love in a Fallen City, The Golden Cangue, Half a Lifelong Romance, and The Rice Sprout Song. All worthy contenders, but the final run-off saw Lust, Caution triumph with more than 65% of the votes. Like Brexit perhaps — technically non-binding — but we’ve gone with the decision anyway. Who are we to argue with the China-reading masses!

But why Lust, Caution among all these great possible choices? Well, there’s the Ang Lee movie obviously, and also possibly that it’s a short novella, but maybe also because it talks about a specific time (the Second Sino-Japanese War) and a specific place (Shanghai), and the strange phenomenon of the Chinese fifth column collaborators around Wang Jingwei — something Chang, thanks to her first husband, who was a collaborator — knew well.

So Lust, Caution it is (I’m currently working from the Julia Lovell translation for Penguin Modern Classics, published in 2007). In addition to providing the source material for Ang Lee’s movie, it is a masterclass in the short story/novella genre. From the start we are plunged into the decadence of Shanghai — “glossily rouged lips,” “sleeveless cheongsams of electric blue,” “diamond studded sapphire button earrings.” But we soon learn that these women are the wives and consorts of the treacherous officials of Wang Jingwei’s pro-Japanese puppet government in 1942. The women around the table are married to smugglers, traitors, chancers, and are themselves not above a little gold smuggling from Hong Kong to their “island” — Japanese-occupied Shanghai, the conditions of which they have accepted and support. Wang’s puppets sit in appropriated European-style houses wearing gold necklaces, playing mahjong for high stakes, and spending their nights in fashionable restaurants. Their gossip centers on who among their treacherous coterie is smuggling, hoarding, speculating most successfully. An affair is underway, a young woman and a senior married official of the Wang regime. They meet in apartments left vacant as their British and American owners have fled or been interned.

Part of the appeal of Lust, Caution, as well as perhaps how Chang is able to recreate wartime Shanghai so vividly (she begun the story in the 1950s and eventually published it in 1979, so we can safely say each sentence is long-considered!), is that she knows of what she writes. Her first husband Hu Lancheng was a propaganda official in the Wang Jingwei government. He betrayed her frequently and eventually fled to Japan for 20 years and then Taiwan to avoid what would have been certain execution for treachery. He died in 1981 in Tokyo. We should also note that her flashback scenes to Hong Kong and her character’s time as a refugee at Hong Kong University are also vivid.

Chang also feels constantly fresh and modern to us, so much so that we can sometimes forget that she was outside the mainstream intellectual modernist tradition of mid-20th-century Shanghai. She is a product of upheaval — her father a grandson of Lǐ Hóngzhāng 李鸿章 — and she herself was born only a few years into the new republic, destined to see warlordism, Japanese aggression, civil war, and communism. Yet Chang remains largely apolitical, saying, “Though my characters are not heroes, they are the ones who bear the burden of our age.”

For such a short tale, Lust, Caution enthralls us in its minutiae of wartime Shanghai life, its espionage plot, and then a final twist. Chang’s heroine/anti-heroine Wang Jiazhi is a product of her times, too. The writing is a masterpiece by any international standards, let alone within the Chinese literary canon. And all along, we know that, though fiction, Lust, Caution is, at least in part, autobiographical (the attempted assassination in the plot was based on the real-life attempt by Shanghai socialite Zheng Pingru to kill Wang Jingwei’s spy chief, Dīng Mòcūn 丁默村), offering us resonances of Chang’s own wartime life and experiences.

Next time:

From a stylish and sophisticated novelist to a man who was equally revered in the interwar years and afterwards for his own cosmopolitanism, representing an urbane, intellectual, and witty China that readers globally responded to enthusiastically…

Check out the other titles on Paul French’s Ultimate China Bookshelf.