‘The Backstreets’ by Perhat Tursun: A Xinjiang novel before its time

"The Backstreets" is a masterful work of stream-of-consciousness fiction that has recently become available outside China, the first Uyghur-language novel to be translated into English.

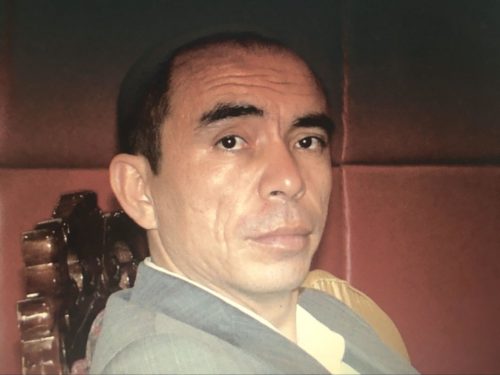

Perhat Tursun is the leading modernist Uyghur-language author alive today.

Along with Tahir Hamut, who also studied literature in Beijing in the 1980s and 1990s, and a handful of other poets and translators, he pioneered an “avant-garde” literary group that took inspiration from existentialist philosophy, psycho-analytic theory, and postcolonial literature. This pushed him to examine issues that were typically not the subject of Uyghur literature and poetry — issues of mental illness, sexuality, religion, and so on. By writing explicitly on themes outside more traditional Islamic and socialist realist themes, he sparked a lot of controversy within the Uyghur literary establishment. This was particularly the case with his 1999 book The Art of Suicide, which some viewed as anti-Islamic. Its publication resulted in him being unofficially blacklisted from presses that published Uyghur-language literature.

Yet as Uyghurs began to explore and translate world philosophy and literature, such as the work of Nietzsche and Toni Morrison, by the mid-2010s Perhat came to be celebrated by many young urban readers as a thinker who was pushing the line of what Uyghurs could say and think among themselves. So just as the Chinese state declared the People’s War on Terror in 2014, he was again becoming one of the most influential Uyghur writers of his generation.

One of the novels he published in this moment of cosmopolitan Uyghur-language cultural flourishing was a masterful work of stream-of-consciousness fiction called The Backstreets, which has recently become available outside China, the first Uyghur-language novel to be translated into English (disclosure: I translated this novel with an anonymous Uyghur who disappeared in 2017). When a friend introduced me to a 2013 edition published on the online Uyghur-language forum called Book Craving, I immediately found its absurdist and evocative prose really moving. It also spoke to the issue I was researching as an ethnographer: how rural migrant Uyghurs live despite the forms of systematic discrimination they experience while navigating settler institutions in the city. The book offered me a way into that lived experience and opened up a whole range of questions about urban alienation that I brought with me into interviews with Uyghur migrants.

Like many of the best works of fiction, the book depicted experiences that were shared by many of its readers, particularly the Uyghur migrants I spoke with and observed. Each migrant’s story was different, but the images and mood that Perhat portrays in the book nevertheless illuminated their experiences. The book follows a day in the life of a young Uyghur man who has been given a temporary job in a government office in the capital of Xinjiang, Urumqi. His smiling Han boss and low-affect coworkers appear to actively conspire to deny him a place to stay in the city, and confronted by a bewildering maze of undecipherable streets, the body-penetrating cold smog of a northern Xinjiang November, the constant scream of tires on pavement, and the blank stares and genocidal chants of the city’s inhabitants, the protagonist struggles to figure out his place and his future. As the Uyghur philosopher Memtimin Ala put it in his reading of the novel, the cold is “a metaphor for vagueness and uncertainty, capturing the essence of Uyghur reality. It is a kind of metaphysical anxiety in the labyrinth of terror.”

The descent into displacement and madness that forms the central trajectory of the novel is punctuated by absurdist observations that the protagonist makes regarding objects and people that he confronts as he stumbles through the streets. At times, they spark memories of his childhood growing up under the shadow of a portrait of Mao Zedong in a village courtyard house in the Uyghur countryside. He remembers the hot breath of first love, the sweet breath of his sorghum liquor-addicted father, the vast clarity of the desert, the songs that farmers sang to measure space, the sheikhs who lived in cemeteries and the female shamans who burned incense for healing, and elaborate, fantastic tales about the city. These too were images that the Uyghurs I interviewed recognized in their own lives.

In some ways, the language and ideas of The Backstreets preceded the text. They did more than what Perhat could have intended. They anticipated the erasure of a Uyghur way of life and the systematic diagnosis of Uyghurs as mentally diseased. The Backstreets is the story of a single Uyghur young man confronting a Chinese city, but for Uyghur readers he represents a derivation of the path of their own lives. And for colonized people elsewhere, the feeling of his story — the promise of social mobility through education and migration, and the reality of systematic discrimination — resonates with the racialized dynamics that signify the experience of modern history for much of the world. Perhaps this is why Elif Batuman, in her endorsement of the book, describes its “style, mood, and scope” as “evocative of Camus (or maybe of an alternative Camus who wrote from an Algerian perspective), while still feeling utterly distinctive and unprecedented.”

Over the 1990s and 2000s, the Uyghur homeland in southern Xinjiang and Urumchi, where the book is set, became the site of a large influx of state-supported Han settlers from other parts of the country. It was during this period when social institutions — ranging from the school and banking system to the local government and legal system — were overrun by these new arrivals. This meant that while some Uyghurs remained in these institutions, the hierarchies of power within these places came to center on Han individuals and values that they brought with them.

During my fieldwork in the region, settlers ranging from taxi drivers to university teachers told me over and over again that they viewed Uyghur migrants and colleagues as “backward” and uncivilized. So this is why — as shown in one scene in the novel — even a Han janitor in a government office could view himself as superior to a Uyghur office worker who spoke non-standard Chinese. Nearly all Uyghurs I interviewed spoke of the way they had been treated with scorn by Han settlers.

The hatred of Uyghurs grew, and the autonomy that Uyghurs were permitted narrowed, over the time that Perhat wrote the novel. This was a reflection of the government policy known as “Open Up the West” and the support for the settler society that this policy fostered. An important moment in this rise in the racialization of Uyghurs came after the large-scale Uyghur protests and riots following a kind of lynching of Uyghur workers at a factory in eastern China in 2009. In the years that followed, the state radically increased the police and military presence in the region, and began a series of “hard strike” campaigns that targeted Uyghurs who were allegedly involved in protests and violence that the state deemed acts of terrorism, or “hate crimes,” toward settlers.

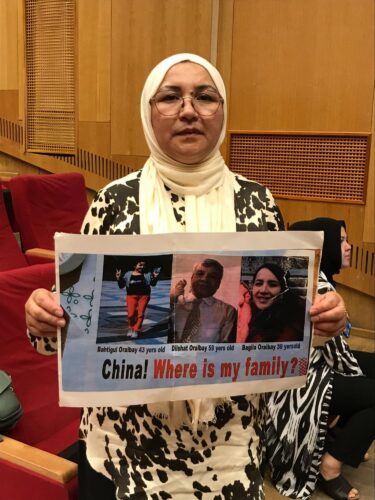

In his work, Perhat is attempting to open a space for reflective thought. He often told me that his only ideology was a suspicion of all ideologies. He was a practicing Muslim and very proud of the creative traditions that Uyghurs deploy to create their social worlds, but he was suspicious of movements that he saw as dogmatic. He saw what people, both Uyghurs and Han, took to be normal life as a kind of madness, and the ability to see and live beyond those structures, what others might see as a kind of madness, as the closest one could come to self-actualization. In the end, state authorities came to see Uyghur freedom of thought as potentially dangerous. This is why, it appears, nearly all of the Uyghurs who participated in the avant-garde literary salons, as well as their Uyghur critics, in more than 300 documented cases, were detained in 2017 and 2018. Perhat himself was allegedly sentenced to 16 years in prison in a secret trial.

In daily life, the policing of Uyghur culture means that Uyghurs must now be guarded when communicating with each other in person or online. It is likely that even mentioning the name “Perhat Tursun,” if noted by an informant or through automated surveillance, could result in an interrogation. When speaking in the presence of Han people, Uyghurs know now that they should strive to speak Chinese as much as possible. They have been given the impossible task of proving their mental and ideological trustworthiness as Chinese citizens.