Xinjiang exit bans keep Uyghur ‘agitators’ in place, divide families

China has dramatically expanded its use of exit bans over the past decade, as many Uyghurs have discovered in the last few years.

Well before 2020, when Beijing ordered all Chinese to stay put to prevent the spread of COVID-19, a series of laws barred mostly Muslim Uyghurs from leaving their homeland in Xinjiang.

A May 2023 report by the Madrid-based human rights advocacy group Safeguard Defenders, Trapped: China’s Expanding Use of Exit Bans, details Beijing’s restrictions on travel outside China by P.R.C. citizens, particularly Uyghurs, through the use of what, effectively, are exit bans controlling the movements of so-called “troublemakers” and their families both in and outside China.

The restrictions, ramped up since 2016, keep Chinese citizens the government calls “agitators” in check throughout the country, effectively imprisoning many Uyghurs in their homeland, an area nearly the size of Alaska, making it difficult for them to reunite with family, friends, and associates living and working outside Xinjiang.

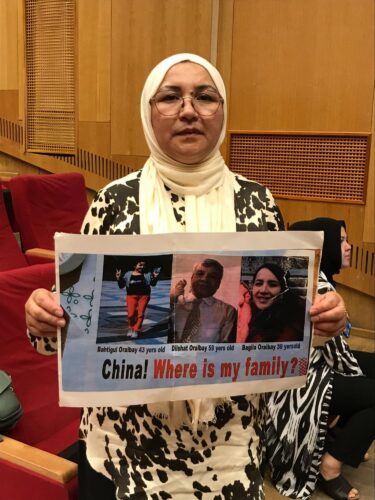

“The heartbreak is constant,” Uyghur Omer Faruh told The China Project from exile in Istanbul. When Faruh’s wife fled Xinjiang in 2016, to join him, she was forced to leave their two infant daughters behind with her parents. The couple have had no contact with the grandparents since, and have heard their elders may have been interned.

Also in 2016, Beijing escalated the mass internment of Uyghurs in so-called reeducation camps. The government confiscated — for “safekeeping” — all Uyghurs’ travel documents. Later, some Uyghurs were found to have been interned for applying for a passport.

“I have no idea who has my children now,” Faruh told The China Project. Though Turkey granted citizenship to the two Uyghur girls in absentia in June 2020, and, that August, Faruh initiated procedures to bring them out, he and his wife are no closer to reunion with their babies.

“We have done everything right and the Turkish embassy in Beijing has requested the Chinese government to let them come to us, but since then, there has been silence,” Faruh said. “Why won’t they let our children join us?”

This frustration is the result of 14 laws and scores of legal interpretations and documents that govern approval to leave Xinjiang, or a visa to leave China, according to the Safeguard Defenders report. The legal jumble that amounts to an exit ban for Uyghurs is legitimized on the grounds of national security and deployed against Uyghurs accused in civil or criminal cases. The bans usually are enforced either at China’s border or by confiscating or denying passports, the report said.

The Chinese laws and their different interpretations are difficult to navigate and effectively trap thousands of citizens accused but not convicted of a crime with no way to travel. Some Uyghurs whose alleged crimes are not covered by one of the 14 laws are stalled in place by broad legal clauses that cover anyone the government deems suspicious, the report said.

Uyghurs trying to travel often only discover their names on an exit ban list when they are about to leave. Bans commonly have no legal basis, appeal is futile, and trying to get them removed is a non-starter, the report said.

A brief history of exit bans

Exit bans have affected China’s ethnic minorities for decades, and typically were employed to prevent religious tourism overseas, such as performing Hajj, Islam’s ritual sojourn to Mecca, in Saudi Arabia. A two-tier system for passport applications has been in effect since 2002, fast-tracking Han Chinese documents in 15 days but delaying — often for years — applications by Uyghurs, Tibetans, and other ethnic minorities. But such exit bans have been on the rise since Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 took charge in 2012.

Human rights groups estimate that at least 14 million people were barred from leaving China in 2015 and that, in 2016, exit bans began to be deployed en masse against minority populations rather than just in isolated individual cases.

Beijing now bars Uyghurs from visiting 26 mostly Muslim-majority countries deemed “sensitive.” In 2016, the government began penalizing some of them retroactively for having visited those countries before they made the list. Uyghurs found to have relatives living in one of the 26 countries on the list (Turkey is included) began to be punished with internment, a practice human rights groups call “transnational repression.”

The exit ban as a tool of Beijing’s control predates its mass internment of Uyghurs. In 2012, China’s government targeted suspects of Xi’s nationwide anti-corruption campaign 反腐败斗争 with exit bans. If suspects already had fled the country, their family members could be denied exit visas as leverage to force the suspects to return. This practice soon was applied beyond the anti-corruption campaign and used as a tool to reel in Uyghurs living in exile in opposition to Beiing’s policies.

Uyghur educator Abduweli Ayup was imprisoned in 2013 after trying to open Uyghur-language kindergartens in Xinjiang. After he was released in 2015, he fled first to Turkey then to Norway, from where he began to travel freely to report stories of the growing suppression of his people inside China, stories he collected from newly exiled Uyghurs.

In 2020, Chinese police pressured Ayup’s brother and sister-in-law to demand that their daughter, his niece, Mihray Erkin, return to Xinjiang from Japan, where she worked in biotech. Upon arriving home, Erkin was immediately interned and died under suspicious circumstances in December that year.

Several other Uyghurs now exiled in Turkey spoke to The China Project about children left behind in China as wards of the Chinese Communist Party.

“The CCP has no right to keep them from us,” said Meryem, who, in 2015, fled China across Southeast Asia with three children, leaving behind in Xinjiang her husband and two more children, both infants, hoping that they would be reunited once the infants had passports. As she fled, Meryem’s husband called to tell her the police were on their way to arrest him. He told her to make a new life in exile with their other children. “What law on earth permits a mother to be separated from her babies?”

In Istanbul, Meryem met a Uyghur man whose wife and children also were forbidden to leave China to join him. They now live together as a new family. “Istanbul is full of people like us,” she told The China Project.

“Other countries do everything they can to reunite missing children with their parents,” Meryem said. “I have lost contact with everyone at home and will never see my babies again.”

Because the Chinese government monitors all electronic communication in and out of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Uyghurs outside China often choose not to contact their relatives back home for fear of endangering them inadvertently. Many Uyghurs still living in their homeland also take defensive action and delete their families’ overseas contacts from their mobile phones and social media accounts.

Expanding exit bans and sending informants abroad

According to the Safeguard Defenders report, exit bans now can be applied not only to citizens of China, but also to international journalists whose reporting on areas such as Xinjiang and Tibet violate China’s recently expanded definition of espionage.

The new legislation has put many foreign nationals working in China on edge. International journalists, already few in number on the ground in northwestern China, now, more than ever, will be deterred from traveling to the region to conduct critical reporting.

China’s expanded definition of espionage will “cripple the flow of accurate news coming from East Turkestan,” Rushan Abbas, the executive director at the Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group The Campaign For Uyghurs, told The China Project, calling Xinjiang by the name many Uyghurs use to describe their homeland.

“The absence of firsthand accounts and objective journalism will only perpetuate the opacity and misinformation surrounding one of the most pressing human rights crises of our time,” Abbas said.

When, in November 2022, an apartment fire in Ürümchi killed several Uyghurs locked down under anti-COVID-19 measures, a wave of protests against Beijing’s much-maligned COVID-zero policy spread across cities elsewhere in China. Crowds of mostly majority Han Chinese protesters gathered in Shanghai on Ürümchi Road and shouted calls for Xi Jinping to step down.

Xi’s response was to unlock homes, and, soon, to allow some individual Uyghurs to apply for passports to travel.

Uyghurs long separated from their families overseas exchanged excited texts on the Chinese social media platform WeChat. Then fear set in. Several Uyghur university students who arrived in Britain and the United States told The China Project that Uyghur compatriots living in the West shunned them upon arrival for fear they might be spies.

Omer Kanat, the director of the Washington-based Uyghur Human Rights Project, warned that only a chosen few Uyghurs were leaving Xinjiang, and that they were doing so under strict Chinese government control.

“They have to swear affidavits, some have to sign their homes over to the government, and they are threatened with [internment] camps on their return if they step over the line,” Kanat told The China Project. “They are all terrified that something will happen to their relatives if they speak out, so most just keep quiet or say that everything is fine over there.”

Kanat said he knew that Beijing was sending select Uyghurs overseas to promote a positive narrative of their homeland.

“No one trusts these people,” Kanat said. “They are all given a wide berth by the Uyghur community.”

China’s use of exit bans contravenes the Convention on the Rights of the Child, Article 10, which China ratified, and which entreats states to “respect the right of the child and his or her parents to leave any country.”

Exit bans also violate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 13, which grants that “everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country,” and similar language in Article 12 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Abbas said the exit bans “not only perpetuate the third stage of genocide — discrimination — but also inflict immense emotional and psychological suffering on families who are torn apart.”

“We urgently call upon the international community to address and condemn these exit bans,” Abbas said.