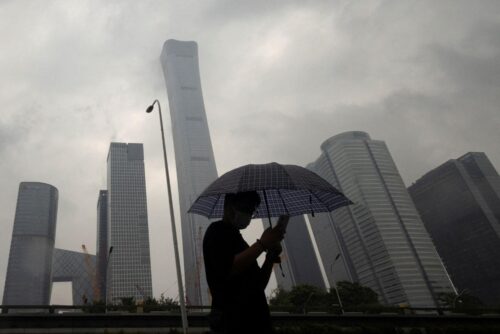

China’s coming COVID tsunami?

Many experts warn that China is facing the possibility of a massive number of deaths from COVID-19.

The stunning pace at which Chinese authorities are loosening up COVID-zero restrictions has lifted economic hopes around the globe, but some are concerned about what might come next. At the end of November, Airfinity, a health analytics firm, published a model suggesting that, over the next three months, if COVID-zero regulations are lifted, China is likely to see 1.3 to 2.1 million deaths from COVID-19, and 167 to 279 million cases.

Another model, published by Chinese scientists in May, predicted that, if COVID-zero restrictions were relaxed, 1.55 million residents of China would die in the three following months in “a tsunami of COVID-19 cases,” with 75% of the fatalities in people over 60 years-old. They also predicted 112.2 million symptomatic cases and 2.7 million ICU admissions, about 15.6 times the number of ICU beds available.

Dr. Katelyn Jetelina, author of the popular newsletter, Your Local Epidemiologist, confirmed to The China Project that this model is valid and that 1.55 million deaths seemed reasonable to her. “Unfortunately, I do see, if COVID-zero is dropped, the potential for a large number of deaths.”

This past week, The Economist released a more conservative prediction, with a model that suggested that only 680,000 people would die from COVID-19 if COVID zero was ended. Yet even these rosy assumptions were predicated on everyone who needed an ICU bed getting it (“which they would not” The Economist pointed out). These models suggest that China should be steeling itself for a winter of death.

There are some experts who see a narrow path to keep the wave from becoming a tsunami, but even they are not all that optimistic. In an article titled “How China can pivot from ‘zero COVID’ while preventing calamity,” Leana Wen, a professor of health policy and management at George Washington University, still hedged as to whether or not China could avoid a large number of casualties: “It’s possible that even with these steps, reopening could result in a tsunami of infections and deaths, especially in rural areas where many people cannot access care.”

The most optimistic assessments of China’s COVID future are from state propaganda organizations, which are talking up China’s “confidence to face the virus directly,” and talking down the deadliness of the Omicron variant. And perhaps the widespread acceptance of facemasks, fear of the virus amongst the elderly, and the understanding — gained over the last three years — of how to treat the disease will help China avoid the worst outcomes. But specialists seem to be overwhelmingly pessimistic.

How China’s ‘magic weapon’ failed

For much of the pandemic, China did an excellent job controlling the virus even as the rest of the world suffered from massive numbers of deaths. But the country’s leadership appears to have been lulled into a false sense of security. Many in the government thought that China could continue to follow the COVID-zero playbook and get the same results, and so they did little to prepare for the inevitable wave that would come when the country ended restrictions.

Today, China is no better prepared for the coming emergency than it was three years ago. “I am confused as to why they didn’t spend those three years differently, Professor Ayo Wahlberg, an anthropologist at the University of Copenhagen who has conducted research on medicine in China, said in an interview. “That really stumps me.”

For most of 2022, China stopped preparing for a post-COVID-zero world, apparently believing that the policy would continue to deliver success. In May, the Deputy Head of the National Health Commission, Lǐ Bīn 李斌 crowed that the COVID-zero policy was China’s “magic weapon” against the virus.

All indications were that Beijing was planning to stick to the COVID-zero policy for the long haul. In May, China canceled plans to host the 2023 Asian Cup soccer tournament, hinting that the policy would still be in place at the time. In late July, bureaucrats in Beijing wondered whether the government should transition from COVID zero to a policy that allowed the country to live with the virus, which reportedly made Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 “furious.” In a message he apparently wrote to his subordinates, he accused them of being “laxed and numbed” in their fight against the virus.

A sudden policy reversal

One of the stranger aspects of China’s complacency about its pandemic policies has been that during 2022, the authorities largely stopped promoting vaccination. At the highpoints of the vaccination campaign, on June 27 and December 28 of 2021, 1.57% and 0.89% of China’s population got a vaccination in their arms in a single day, respectively. But for much of 2022, that number hovered well below 0.1%. This is strikingly low, considering that experts are now warning that China’s only hope of avoiding large numbers of deaths is to implement an ambitious vaccination campaign.

Chart for The China Project by Nadya Yeh; date source: Our World in Data.

But until the end of November, Beijing gave no indication it was ready to roll back COVID zero. On November 11, the government released a revision of the policy which eased up around the edges but kept the main restrictions in place. And in late November, European diplomats visited a factory that was supposed to be producing COVID-19 vaccines; they were troubled to find the factory idle, with no indication that Beijing was ramping up production. Even as late as November 24, the Financial Times reported that an unnamed official close to the Chinese Centers for Disease Control and Prevention stated explicitly that COVID zero would continue: “There is no way we can open up right now.”

But two weeks later, it did just that. At the end of November, protests broke out across multiple Chinese cities. The proximate cause was a fire in an Urumqi apartment building in which at least 10 people died, apparently unable to evacuate because of quarantine measures, but pressure had been building up. When Chinese soccer fans watched the World Cup, many found themselves asking why spectators in Qatar were allowed to cheer unmasked while large numbers in China were still locked down. Professor Wahlberg calls this “the World Cup Effect.”

In a news conference on December 7, Li Bin acknowledged that the protestors had been part of the reason for the change, saying that “the masses had reacted strongly” to the November 11 revisions of the policy and that its “implementation was not up to standard and was not precise and had other problems.”

High vaccination numbers hide China’s vulnerability

Ostensibly, Beijing did an excellent job with vaccinations. As of December 6, China had administered 2.41 doses of vaccines per person, while the U.S. had given only 1.97 doses per person. Upwards of 90% of China’s population has been vaccinated with the first two shots. These suggest that China should be well placed to ease pandemic restrictions. However, China’s vaccination program has been dogged by two main problems.

First, even though China’s overall number of vaccinated individuals is high, only 65.8% of those over 80 years-old have been vaccinated with the primary series. For several months at the beginning of the rollout, Beijing refused to vaccinate those over 60 years-old, signaling that it was not confident the shots were safe for older people (there is no scientific evidence which supports this erroneous belief). Even afterwards, doctors continued to discourage the elderly from getting vaccines. In July, Beijing’s city government did attempt to impose a vaccine mandate on those living in elderly-care homes. Within hours, there was significant pushback on social media. The next day, the government backed away from its mandate, most likely because vaccine-skeptical retired cadres used their influence within the Party.

Second, China has been unwilling to acknowledge that its vaccines are not as good as the mRNA vaccines favored by the rest of the world. Zhōng Nánshān 钟南山, the pointman in the country’s pandemic response, stated that China’s vaccines are “as good as Pfizer’s in terms of their efficacy.” According to experts outside China, that is not true. Last week, Ashish Jha, Zhong’s American counterpart, said that Chinese-made vaccines are “not as good” as the mRNA shots. The antibodies triggered by Beijing’s vaccines drop to low or undetectable levels after just six months. Unlike the mRNA vaccines, China’s vaccines require a third dose to be effective against severe disease; only 40% of those over 80 years-old have received that third dose.

But Beijing only approved non-Chinese jabs for foreigners last month, and it still has not approved them for Chinese citizens. Airfinity estimates that, because of these weaknesses, and also because Beijing had done such a good job of keeping the virus out, less than 10% of China’s population has protection against Omicron infection.

Chart for The China Project by Nadya Yeh; data source Airfinity using a model that estimates immunity levels in a population based on prior infections and vaccinations, taking into account waning immunity.

Not enough hospital beds

These are compounded by the other problems affecting China’s medical system. Overall, China’s medical professionals are poorly trained; only 58% of doctors have any university degree at all. Mainland China also has a shortage of intensive care unit (ICU) beds. A 2020 study showed that the country had only 3.6 critical care beds per thousand residents, half the ratio that Hong Kong had when the territory saw bodies piling up in hospitals. Efforts to rectify the problem in China have been desultory; despite claims that it was preparing for medical emergencies, Beijing increased the number of critical care beds by only 3.8% in the year that followed. All of this is happening as many of the country’s private hospitals are closing.

When The China Project asked Professor Wahlberg whether or not China could do anything to stop this, he said, “It’s kind of too late.” There is little that can be done to prevent a large number of deaths if China opens up despite being behind in its vaccination goals, particularly considering how contagious Omicron is. Referring to the Delta wave that clobbered much of India in spring 2021, he said, “I expect what happened in New Delhi to happen in a lot of cities in China.”

We can only hope he is wrong.