“Art brut” is an artistic concept birthed in France in the mid-20th century, inspired by the art of outsiders, often those with mental health conditions. In China, one person has made it his life’s work to highlight the dignity and artistry of its practitioners.

It often rains in Nanjing. Not in autumn though. At least it shouldn’t.

The day I visited, during the National Day holiday commemorating the 67th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China in October 2016, I was not welcomed by warmth and osmanthus scents but a moist asphalt and constant drizzle. There was a thick sense of expectation as I trudged through the tangled streets of Nanjing, dodging vehicles and assaulted by car horns, with an address in my pocket.

At the time, I had been casually looking into the topic of Chinese art brut — the art of, according to one definition, “the psychotic, the naive, and the primitive” — for the past year. There were many dead-end sources and 404 screens during my research, but I found one website worth my attention: that of the Nanjing Outsider Art Center, which featured a coherent introduction of the center, including its history, and images of artworks, including bibliographies of artists. It listed upcoming exhibitions and events and, importantly, it offered an address. There I was headed, and there I was ready to obtain answers on the history and peculiarities of Chinese art brut, 原生艺术 yuánshēng yìshù, with the man who was said to be its pioneer, monsieur Guō Hǎipíng 郭海平.

That day I arrived in the rain, though, I couldn’t find any trace of the center. I stood in a relatively humble and anonymous residential neighborhood blurred by a thick drizzle that could have been painted by a watercolorist. The more I looked, the less I saw. Someone had spotted me, though. A lively woman in her 50s, maybe 60s, approached, emanating a rippling warmth. “Of course I know the Nanjing Outsider Art Center!” she said. “My son is a habitué. He is an artist!” Her son is Yáng Mín 杨旻, a young man diagnosed with schizophrenia in 2002 who was hospitalized several times during the following decade. Yang Min met Guo Haiping in 2014 and hasn’t stopped making art since then. The very first painting he produced after being dismissed from a psychiatric clinic for the last time in mid-2014 was a man tied to a hospital bed, undergoing a session of electroconvulsive therapy.

“The center is closed today, I stopped by to pick up a couple of things. What a coincidence!” the woman chirped merrily. The center, it turns out, was properly disguised, with only a small sign to indicate that it was an atelier, as opposed to an apartment or office.

“You want to talk to Guo Haiping? Let me drive you to him,” the woman offered. She was a Nanjinger personally involved in the work of the center. I hopped in her car and off we went toward the Nanjing Museum of Fine Arts, a 25-minute ride south and across the river. It was opposite that building that we approached a pretty cafe, where Guo was working on a small exhibition.

Guo Haiping looked just like in the pictures I had found on Baidu. He wore a black leather jacket and sported a rocky goatee, with reading glasses above large nostrils on an oval face that sagged, as if weighed down by gravity. As I approached, I had no idea that the following encounter would shape the next seven years of my life. I could already perceive his charisma though: spontaneous, inadvertent, contagious, and invigorating. As he saw me and smiled some words of welcome, his spell was cast. There I was, orbiting with the room in which he was the center.

He spoke boisterously. “What brings you to Nanjing? And how did you find us? Fantastic!”

Before arriving, I had been full of questions. But at the cafe, I felt empty. What did I actually know about Chinese art brut? That it existed, that Guo Haiping was its pioneer, that it was active. And about Guo Haiping? That he had founded the Nanjing Outsider Art Center in 2010. What else? What did I even know about China? Never enough, no doubt. Not ready to ask the right questions, I improvised.

It’s a pleasure to meet you. “What brings you to Nanjing?” You! “And how did you find out about our existence?” Baidu. “Really?!” Really! “Perfect timing!” Really? “We are organizing an exhibition with a Dutch museum.” Really?! “Yes! Will you come? In three days! Do you have to leave? Change your ticket!”

And so I did. I changed my train ticket.

“Art can drive you mad, literally”

Guo Haiping was born in Nanjing in 1962, the first of two boys. From a very young age, he interrogated himself about the motions of the soul. His younger brother was diagnosed with schizophrenia when they were young, which shaped both his personal life and professional career. While in his 20s, Guo connected with local artists and was pulled into their circle. From there, he embarked on a bohemian life, and began reflecting on the relationship between art and the psyche.

As we talked in the cafe, Guo handed me his book, Notes on Outsider Art in China (中国原生艺术手记 zhōngguó yuánshēng yìshù shǒujì), published in 2014 by Shanghai University Press. “Why do we interest you? Are you an outsider artist too? You are not? Well, maybe someone in your family? No? But how? How strange!” He told me that he focuses on not only art brut in the strictest sense of the term — art made by those not educated within the art world — but especially the art produced by people with mental health conditions.

First coined by the French artist Jean Dubuffet in 1945 after reading The Art of the Insane by the Swiss psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn, the French term art brut literally means “raw art”; Dubuffet compared it to raw gold: “I like it better as a nugget than as a watch casing.” It refers to works created by self-taught artists often on the fringes of society, in contrast to what Dubuffet referred to as “cultural art,” i.e., art driven by academies. In 1972, the French expression was revisited by the art critic Roger Cardinal and turned into “outsider art” to stress the agents rather than their derivatives, though he included “many examples drawn from the L’Art brut collection of Jean Dubuffet: paintings, drawing and sculptures by schizophrenics, also works by uneducated, innocent artists, such as hermits and mediums.”

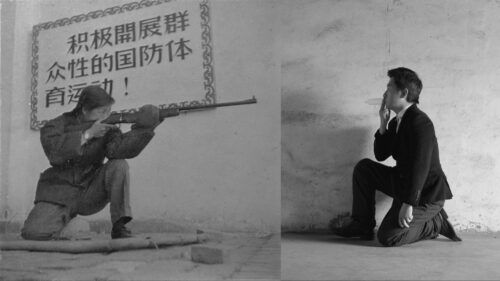

Guo was not aware of any of this happening in Europe, though. As he committed to experimental art in the ’80s, during his mostly modest and rebellious years, he had just started thinking about the relationship between art and the psyche. When the mental health conditions of a close friend showed symptoms of deterioration, he decided he needed to search deeper for answers, and use his work to confront the topic of “mental illness.”

This need only intensified as art — especially the making of it — began to affect him mentally. It had a strong impact, whether positive or negative, on his moods and mental state.

“Art can drive you mad, literally,” he told me. “It can help you improve your mood or find relief during depressive states, but it can also lead you to complete sublimation. And complete sublimation means annihilation.”

Motivated also by his brother’s experience of the onset of schizophrenia during the Cultural Revolution, Guo’s interest in mental health turned him into a key player in the development of the first psychological counseling services offered by the Nanjing municipality in 1989: a daily hotline, available from noon to 2 p.m., dedicated to helping youth who needed someone to talk to. Little did he know that, from a tiny announcement published in the Nanjing Daily, the phone line would be set on fire. It soon became evident that the city needed more than a simple hotline to meet the demand for counseling services in a country that was undergoing change at a dangerously fast pace.

After four years, as decreasing investments in the service curbed any further development, Guo decided to take his work elsewhere. He opened a “café littéraire” (Guo only speaks Chinese, but he said this to me in French) called Banpo Village near Nanjing University, which soon became a meeting point for local artists and poets.

But more than a decade later, he felt like he still hadn’t succeeded in his personal quest to better understand the arts, the psyche, and the link between the two. He continued his pursuit. His exploration of mental health took him where few dared to go — into psychiatric institutes. In 2006, he spent three months at Zutangshan Psychiatric Hospital, opened in 1952 in Nanjing, to create and operate a temporary studio for the clinic’s patients. He carefully observed the changes in their behaviors, in the colors of their canvases, in the refinement in their drawings, and recorded everything in a diary. What he discovered set in motion the beginnings of Chinese art brut, and the hodgepodge of Guo’s thoughts and observations on the Zutangshan artists’ works turned into his first book, Demented Art: Report on Chinese Mental Patients’ Art (癫狂的艺术 – 中国精神病人艺术报告 diānkuáng de yìshù: Zhōngguó jīngshén bìngrén yìshù bàogào), published in 2007.

“If I hadn’t entered Zutangshan, I would have never discovered what art means and how it connects with our psyche,” Guo said. “I would have never discovered art brut.”

The art of Chinese mental patients

Wáng Jūn 王军, born in 1957, started displaying symptoms of mental illness after turning 40. His wife left him in 2002 with their son after she could no longer tolerate his violent behavior and his paranoia. He was admitted into the Ma’an Shan Mental Health Hospital five times before he finally checked into Zutangshan Psychiatric Hospital in May 2006 under the orders of his village committee leaders and the local police department, for he was deemed a threat to public safety. He was administered 250 mg of clozapine every day.

It was there that Wang met Guo Haiping. In the past, Wang turned to art as an outlet during depressive episodes. He loved depicting massive machines, mostly agricultural machinery from a bird’s eye view — because they were stronger and more resilient than him, Guo guessed, he who was worn down by a life of financial hardship and social pressure. Or, who knows, maybe he favored a zoomed-out perspective because he felt disconnected from society as well as from his own body.

Other times, Wang depicted details of his life in the village, such as in the drawing “Cabinet.”

Wang missed home. When Guo suggested to him that the hospital was better for him because life at home was characterized by stress and unhappiness, Wang countered, “At least I’d be free at home.” Guo had no reply to that.

Wang is one of several patients who benefited from Guo’s studio. Zhāng Yùbǎo 张玉宝, diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, did too. The first two months after Guo created the studio, Zhang visited almost every day. He painted and drew despite having no prior experience. Pain, constriction, deformity, and fragmentation marked his early drawings, as seen in “Struggle” and “Roar.”

“Half-Length Portrait with a Hook” shows half of a silhouette. “I keep thinking about the other half, but I can’t remember it,” Zhang said in frustration.

Zhang’s mental state improved to such an extent that his doses of medication decreased. Even the medical staff was stunned at his rapid turnaround. Interestingly, the subjects of his works also changed. Human miniatures started populating his paintings, perhaps because he imagined himself flying over the scenes, or perhaps because he associated mankind with ants, tiny and insignificant.

As it also happened to other patients, a kind of “artist’s block” struck him after about a month, Guo notes in his book, “a block that he was able to overcome only by producing copies of Egon Schiele’s paintings for two weeks straight.”

From his experience at Zutangshan, Guo got the idea to establish a physical space for outsider artists to create outside of psychiatric hospitals. Three years later, he made it happen. The Nanjing Outsider Art Center (南京原生艺术中心 Nánjīng yuánshēng yìshù zhōngxīn) was officially registered as a privately-owned non-profit organization at the Bureau of Civil Affairs of Jianye District on August 20, 2010.

Art brut and outsider art in China

Two years before Guo established the studio at Zutangshan Psychiatric Hospital, the Taiwanese scholar Hóng Mǐzhēn 洪米贞 published a book about the history of art brut, The Story of Art Brut (原生艺术的故事 yuánshēng yìshù de gùshì), where the term “art brut” is translated into Chinese as yuansheng yishu for the first time. “Yuansheng” literally means “raw” or “native.” Was it yuansheng yishu that the Zutangshan patients were making? Or was it something else entirely, something that could reflect the peculiarities of the Chinese environment where artists could (or could not) thrive?

As Guo wrote in his 2014 book Notes on Outsider Art in China, the term “yuansheng” personifies the need to return to art that is reflective of our genuine selves and that distances itself from the “cultural arts,” as per Dubuffet’s definition. “We have to go back to be in touch with nature, with our true selves, with the real world,” he told me.

I asked him about the translation of the term. Couldn’t “outsider art” — which appears in the English title of his book and his art center — be translated more directly as jièwài yìshù 界外艺术? Why “yuansheng,” i.e., “native art”?

“What good would it do to expose outsiders as such?” he answered. “Perhaps it would be more direct, tangible, easier to understand for the Chinese public. At the same time, it would make itself vulnerable to stigmatization and skepticism. If I introduced you to my friends by calling you ‘an outsider,’ then you would probably be on the guard, right?”

As for “outsider art” being the official English translation of his book and the name of his studio established in 2010, Guo offered a practical explanation. “To speak to a wider audience and give us more chances to be heard, also abroad,” he said.

Part of the reason for my questioning is because — at the risk of causing confusion — there is a concept of “outsider art” that, in China, has a completely different translation than art brut: 素人艺术 sùrén yìshù, literally, “the art of the ordinaries.” This form began to make a name for itself in China thanks to the efforts of a determined art history scholar, Sammi Liu, who formulated suren yishu and started promoting it as such.

Suren yishu was formally inaugurated to the public in 2015 with the Almost Art Project in Beijing. Aimed at carving out a space for itself in the strict contemporary Chinese art scene, Sammi Liu’s suren yishu represented the attempt to create an alternative yet respected school of art. Suren yishu promotes absolute freedom of expression in forms, tools, and concepts while veering away from the utilitarian logic of academia and the market. While there are differences between suren yishu and yuansheng yishu, they are aligned closely enough that collaborations have occurred. Thanks to joint efforts, Chinese “outsider art” has found its footing on a national and international level.

Going abroad is of deep interest to Guo Haiping as well. In July 2015, 100 works by 18 studio artists were shown at the Milan Expo. More were featured at the Outsider Art Fair in Paris in 2018 as well as at the exhibition L’Art brut en Chine at the Galerie Polysémie of Marseille. In the same year, Guo was invited to the symposium “Eye Eye Nose Mouth: Art, Disability, and Mental Illness,” organized by the Asia Center of Harvard University. In 2016, when I arrived in Nanjing, Guo was working on an exhibition in collaboration with the Outsider Art Museum in Amsterdam, aimed at displaying and exploring the differences between the works of Dutch and Nanjing outsider artists.

Art as healing, art as annihilation

In a sense, Guo may be the captain of a small boat of vigorous rowers, ready to be at sea for years in a quest for an island that welcomes their creative determination and sense of personal dignity. But he wasn’t the first or only person to realize the potential of this kind of art, even if he seems to be Chinese art brut’s most passionate spokesperson.

When Guō Fèngyí 郭凤怡 (no relation to Guo Haiping), born in 1942, experienced the acute onset of arthritis in 1989, she couldn’t have known that this episode would eventually lead her into the art world. Forced to retire from the factory she was working at and devoid of any formal higher education, she embraced qigong, a traditional Chinese practice involving breathing exercises and meditation, whose goal is to cultivate the qi, one’s energy and life force, therapeutic for both physical and psychological ailments. Practicing qigong triggered visions, prompting her to start drawing. She depicted Chinese cosmology, mythology, philosophy, and traditional Chinese medicine on calendars, rice paper, and other improvised materials. She gave shape to her creative outflow and found relief from persistent anxiety.

In 2002, the Long March Space gallery in Beijing organized an exhibition of her art, which gained national and international attention. Her works have now been exhibited at the Taipei Biennale (2006), the Museum of Everything (London 2009), and, after she died in 2010, the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013. In 2020, the Drawing Center in New York introduced her work to American audiences with the exhibition To See from a Distance. Another exhibition of her work, Cosmic Meridians, opened on January 7, 2023 at Long March Space.

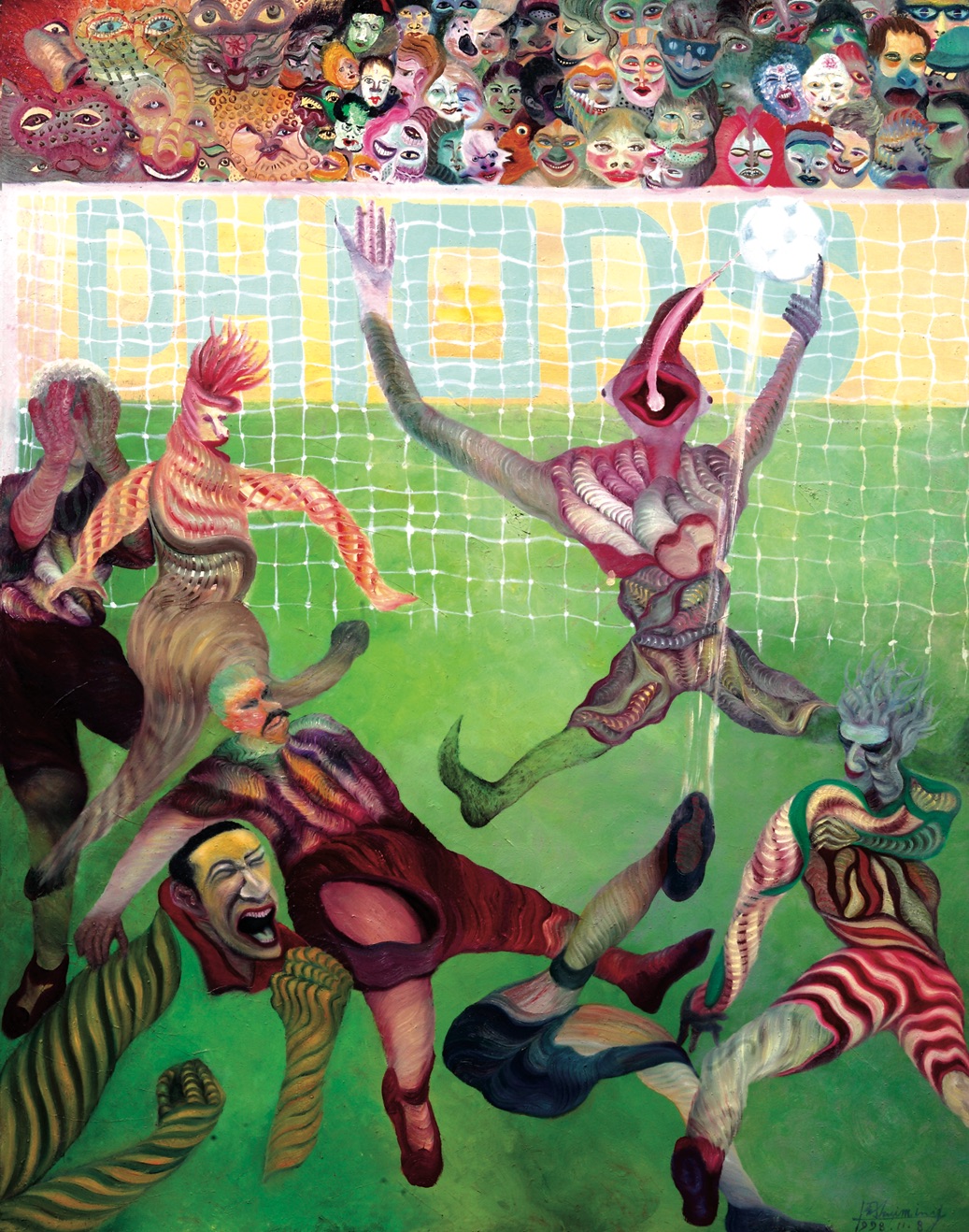

Yet another early practitioner in the field of Chinese art brut was Zhōu Huìmíng 周惠明, born in 1954, “the Chinese Van Gogh,” in Guo’s words. Eccentric, talented, and schizophrenic, Zhou has been the centerpiece of numerous exhibitions thanks to his uninhibited canvases, which he uses as a vessel to transition between his conscious and unconscious experiences, between reality and surreality. Declared “cured” after several years of treatments, he greatly enjoys the degree of creative freedom he can achieve by being “outside” of society.

Is the relationship between society and art mutually exclusive, then? One cannot be truthful to the art and at the same time also be part of society. Does this apply to everyone?

“It’s one of the hardest things to achieve,” Guo said. “It requires one to swing between two sides.” He meant dichotomies like real and surreal, mundane and spiritual, sane and insane. “The biggest difference between an artist and a psychiatric patient is that an artist can access the deepest parts of her psyche and come back, while a psychiatric patient cannot.”

Can you do the same? I asked.

“I can, because art annihilated me once before. In the early ’80s, I lost myself, I had no perception of the difference between life and death. But I came back.”

I spoke to Guo several times after my initial visit, as the Nanjing Outsider Art Center became the focus of my Master’s thesis at the Free University of Berlin. I saw Guo again a year later. Never stingy with ideas and anecdotes, he never bid farewell, as we both knew we would see each other again. But a year later, life got in the way, I moved out of China, and we briefly lost touch. When I returned to China in 2018, I was no longer studying, and then the pandemic happened. And then six years went by.

“Art has given me dignity”

I returned to Nanjing last month, after China dismantled its COVID-zero policy. I was again greeted by rain, but at least I expected it this time. The city center, closed on-and-off due to COVID, didn’t feel much different, though a couple of bars and restaurants had disappeared. Surprisingly, I found the Outsider Art Center to be stronger and healthier than ever: they started receiving financial support from the Nanjing Disabled Persons’ Federation in 2018. In May 2022, Guo also joined the the Therapeutic Outsider Art Workshop, sponsored by the Shenzhen Disabled Persons’ Federation.

I contacted Guo and we met up at a local restaurant he often frequents. He hadn’t changed much. Although slightly silvered by the years, he maintained the same strength and energy that distinguished him the first time I met him. Four dishes and four hours passed by, rarely with a moment of silence. Guo had not slowed down in his pursuit of more recognition for Chinese outsider art, and he was eager to tell me all about it.

“I am promoting a specific kind of art, ‘art brut therapy,’” Guo said. “It’s unique, applicable to different cultures, different artistic and medical disciplines. Art brut therapy allows one to bring to light the true value of art and to serve people from a medical and societal point of view, too.”

I also met again with the woman who first drove me to Guo Haiping all those years back, and her son, Yang Min, a prolific artist and courageous communicator of his mental health experiences.

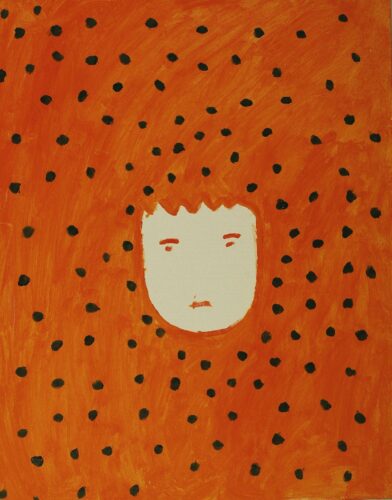

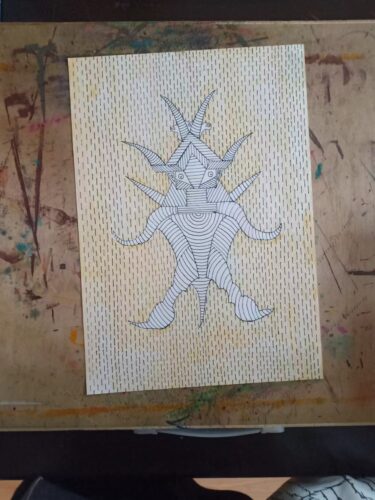

Among the city’s studio artists, Yang has the most severe case of schizophrenia. When I first met him in 2016, his vision was blurred and he spoke in staggered sentences, as he had recently been receiving invasive psychiatric treatment. His art was populated almost exclusively by spider-like creatures.

He seemed better this time. We sat in Guo Haiping’s other studio in Gulou District, the Nanjing Gulou Outsider Art Center, damp and cold due to a lack of central heating, along with Guo and his mother. All three of them were their warm selves, full of courtesy and conversation.

Yang Min, though, stood out. He still draws spider-like creatures, interspersed with dreamy, crowded landscapes. But there was something about his eyes, which were sharp, and his face, showing all the lines of someone in his 40s, and his manners, the well-placed silences and reactions to what I was saying, that made me feel welcomed and seen.

“I live alone now,” Yang said. “I cook and I take my medicines every day without any help. I keep making art, especially when I start thinking too much or when I feel too much. It happened a few days ago, too, so I started drawing, and that helped me clear my mind. Art has given me dignity, something I thought I couldn’t claim for myself.”

I asked Guo what his happiest moment was in the 17 years he’s spent trying to promote Chinese outsider art. He identified his stay at Zutangshan Psychiatric Hospital as his most moving period, but he told me that the happiest is yet to come: when he creates a museum for Chinese outsider art.

Do you ever get tired of doing this, or feel like giving up? I asked.

“I often do,” he replied. “But I cannot give up. When I think about quitting, I ask myself what will happen to the artists and to outsider art. And that works — I don’t give up.”