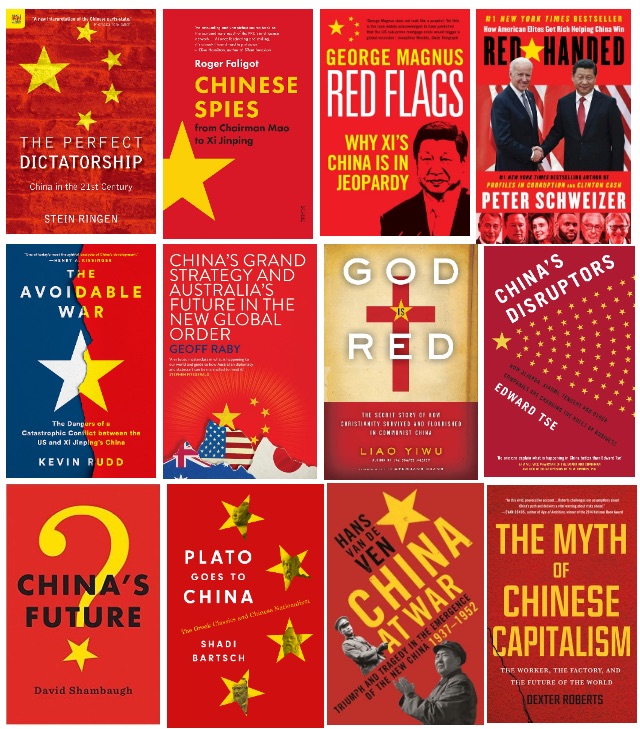

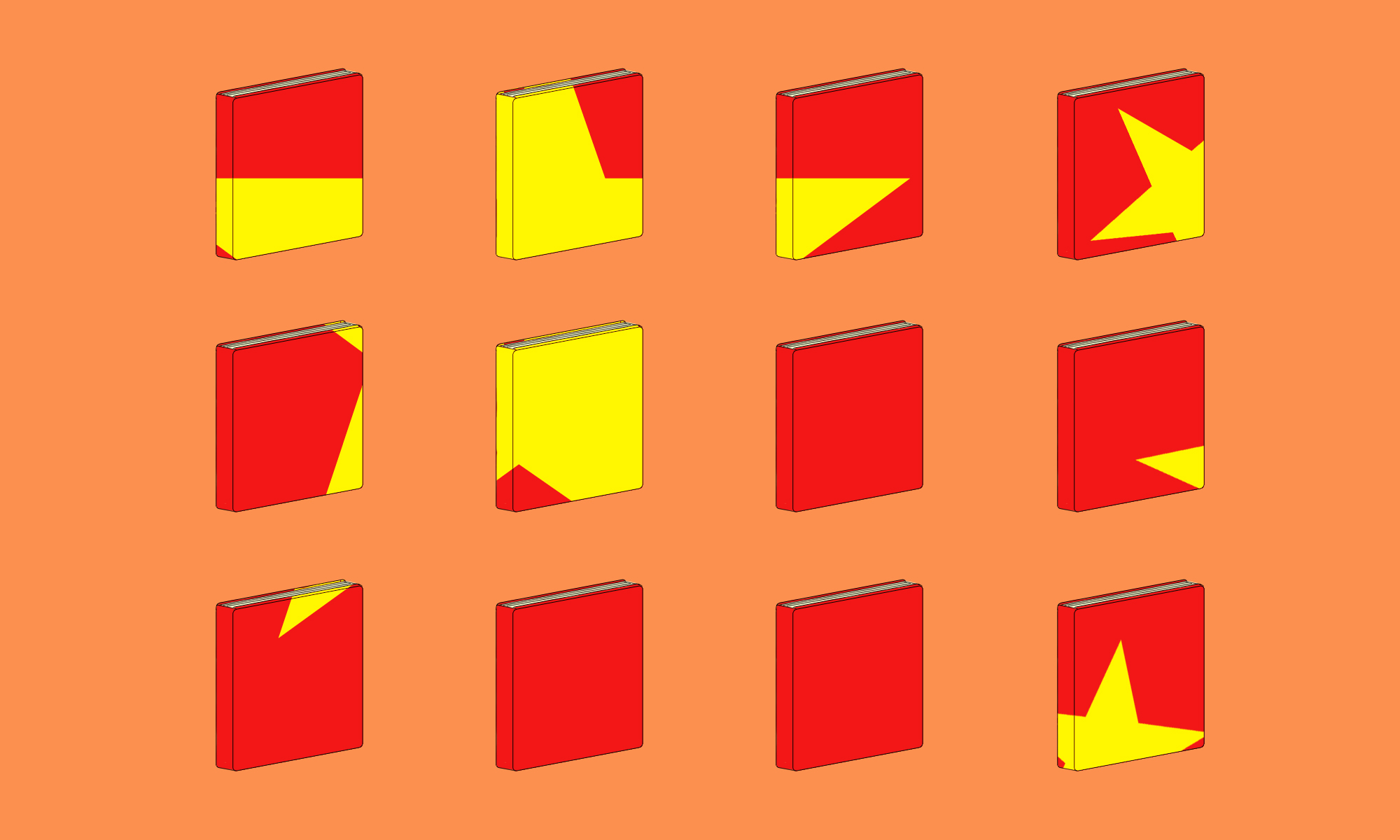

The color red, dragons, cropped Asian faces…when it comes to presenting China, book publishers often rely on a set of familiar tropes — to the detriment of the authors and the genre.

It’s not hard to spot the China section at your local bookstore: shelves stacked with red books have a tendency to catch the eye of even the most myopic browsers from across the room.

Former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s The Avoidable War.

Noted China scholar David Shambaugh’s China’s Future.

Business journalist (and The China Project contributor) Dexter Roberts’s The Myth of Chinese Capitalism.

Just to name a few…

While red jackets have become a mainstay of China books, they appear to be most frequently accompanied by large yellow stars and block writing — part of a visual aesthetic that journalist Selina Lee and researcher Ramona Li have recently dubbed “authorientalism” due to its repeated association with Chinese state power and suppression.

But look again at the selection of books above. One could easily be forgiven for failing to realize that these books explore topics as diverse as Christianity (Liao Yiwu’s God Red), the Sino-Japanese and Chinese civil wars (Hans van de Ven’s China at War), the influence of classical Greek philosophy on Chinese nationalism (Shadi Bartsch’s Plato Goes to China), and the rise of tech companies like Xiaomi and Alibaba (Edward Tse’s China’s Disruptors).

Is it fair that these titles are given the same aesthetic presentation as Stein Ringen’s The Perfect Dictatorship and Roger Faligot’s Chinese Spies?

China news, weekly.

Sign up for The China Project’s weekly newsletter, our free roundup of the most important China stories.

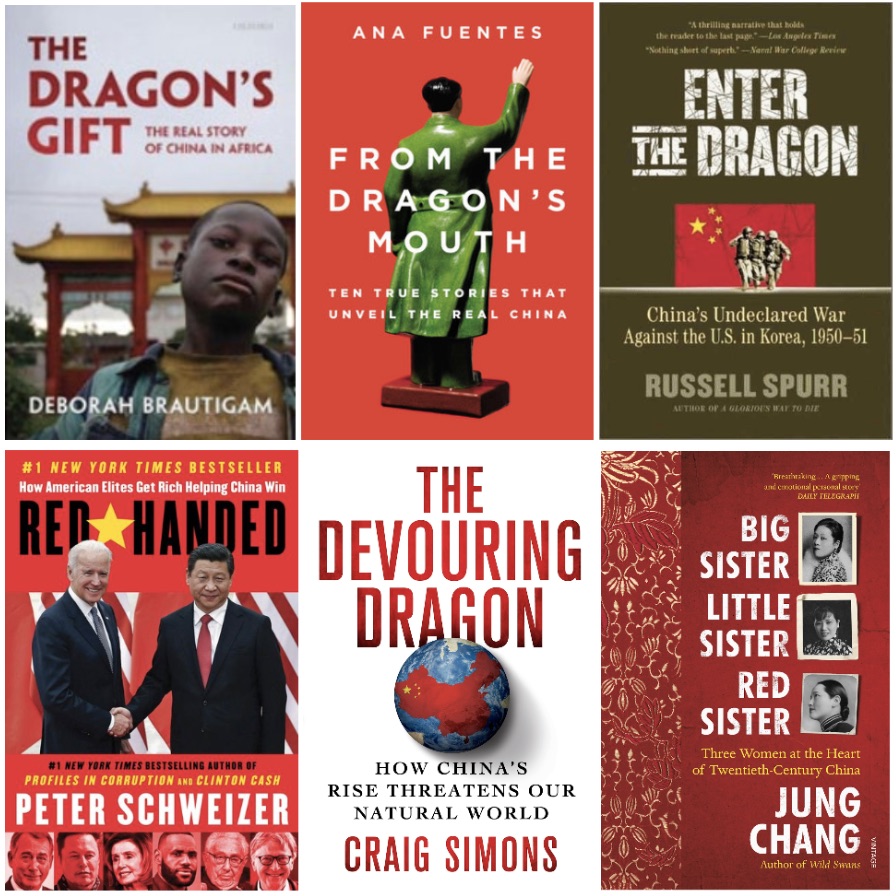

Another frequently seen cover motif is the illustrated dragon.

The jackets of businessman Desmond Shum’s Red Roulette and Michael Wood’s The Story of China both feature elaborate dragons, yellow titles, and red backgrounds. The former is a ghost-written memoir chronicling corruption among China’s contemporary elites, while the latter is a grand narrative traversing thousands of years of Chinese history.

Plays on dragons and the color red also make their way into titles themselves.

Peter Schweizer’s Red-Handed, Jung Chung’s Big Sister, Little Sister, Red Sister (an apparent reference to the popular children’s book Big Sister, Little Sister), Deborah Brautigam’s The Dragon’s Gift, Russell Spurr’s Enter the Dragon, Ana Fuentes’s From the Dragon’s Mouth, and Craig Simons’s The Devouring Dragon are just a few examples.

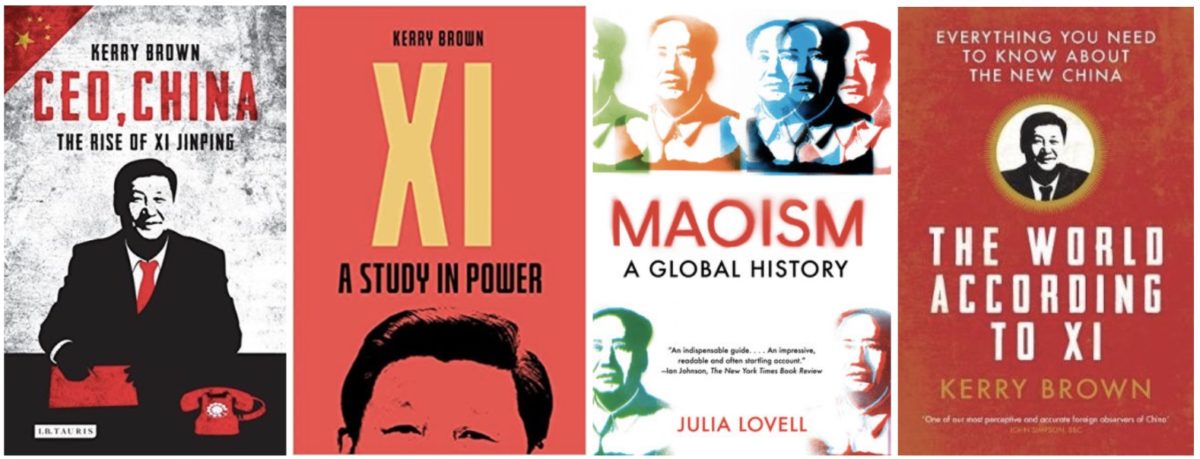

Stylized images of Chinese leaders reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s depictions of Máo Zédōng 毛泽东 have also become a popular front-cover motif. Black Warhol-esque renderings of Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 appear on the covers of Kerry Brown’s Xi: A Study in Power, CEO China, and The World According to Xi, as well as George Magnus’s Red Flags. A series of pop art Mao Zedongs also appear on the jacket of Julia Lovell’s 2019 Maoism: A Global History.

Why, exactly, do so many books exploring different aspects of China have essentially the same cover designs?

Jo Lusby, the former managing director of Penguin Books North Asia, explains that such design choices make a book easily identifiable as being on a particular topic.

“The sad reality of publishing is that it’s an industry of pigeonholes,” she says. “And books have to sit in an easily defined sort of shorthand so that they can make it through the massive system from acquisition by an editor to successful sale into a bookshop and into somebody’s hands.

“That’s why the shorthand evolves.”

Lusby explains that red, as a color, represents both communism and traditional Chinese culture, and sends a clear signal to potential readers from halfway across the room.

Lusby also points out that with a lot of books about China, the topic and content of the book may have more resonance with the potential reader than the authors themselves, hence publishers’ desires to make the subject matter easily identifiable.

While such designs may initially help communicate the broad topic area to potential readers, it also means many books, despite having diverse content, end up looking indistinguishable.

“The problem comes when the books start all looking the same,” she says, “and you can’t differentiate, when actually these books are very different and have very different subject matter, very different tone, and very different content. It’s not particularly helpful if you’re trying to get beyond stereotypes…and trying to present very different views and very different perspectives on a very complex place, and all the [book] jackets fit into a couple of simple templates. You’re not expressing that diversity properly.”

Alec Ash, the Yunnan-based author of the 2016 nonfiction book Wish Lanterns, says that the trend is only getting worse as more books on China, particularly those opting to take a bird’s-eye view of the country, are published. “China is being othered even more now, in different ways than it was 20 years ago when people still didn’t know much about it, because of current trends in politics,” he says.

Selina Lee and Ramona Li have pointed out that the repeated use of visual tropes in publications about China are not only homogenizing but also misleading. They argue that the authorientalism aesthetic “distorts and flattens the reader’s view of China and Chinese people” by conflating the current government with Chinese culture and history more broadly. It also implies that authoritarian politics is somehow unique to China.

Ash agrees, noting that while China has always been exoticized, more recent cover designs have moved away from emphasizing China’s perceived “weirdness” and poverty, and instead depict China as a threat. Such cover designs are dehumanizing and feed into an “us versus them” narrative that plays on readers’ fears of China as an enemy Other, says Ash.

“The problem comes when the books start all looking the same…when actually these books are very different.”

But red jackets with yellow stars is not the only problematic China book trope.

Novels set in China, and Asia more generally, have a tendency to feature Asian women with cropped faces on their covers, says Lusby.

“On fiction, you get a lot of headless Asian women and a lovely neck and hair, but no face, no identity…It’s the generic faceless woman trope.”

Lusby says while such designs may have originally been intended to be complimentary, in reality they end up having the opposite effect. “It’s the Orientalist romanticized ideal of Asian women as a target of desire in the Western eye. It’s the Western male gaze,” she says.

“I think it was intended as a compliment at the beginning. You know, look how gorgeous these exotic women are with the swoop of the body and the qipao or the kimono or whatever clothing they have them in. It started as a compliment, but they’re all anonymized…They don’t stand for something individualized, or something with agency or something actualized. It’s not a feminist reading if you don’t ascribe a personality to somebody.”

Lusby notes that such stereotyping is hardly limited to books about China, and points to the example of books set in Africa that have almost identical burnt-orange covers.

Other publishing industry beliefs also influence design choices, Lusby says, such as the common refrain that “green books don’t sell.”

But at least one bestselling author on China has debunked this myth: Jung Chang. Her Mao Zedong biography, Mao: The Unknown Story (co-written with Jon Halliday), and Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, which chronicles her own family history, have both been published with pale green covers (though later editions of both books have also been published with red jackets). Mao: The Unknown Story quickly became a bestseller following its 2005 release, and Wild Swans has sold over 12 million copies since it was published in 1991.

And there are other China titles that stand out for their distinctive cover designs.

Lusby notes that Ài Wèiwèi’s 艾未未 2021 memoir, 1000 Years of Joys and Sorrows, features an illustrated black jacket designed by Ai Weiwei himself.

Another example is Peter Hessler’s China trilogy, which chronicles the writer’s 10 years in the country between 1996 and 2007.

How have these two authors escaped the red jacket trope?

In the case of Ai Weiwei, Lusby points out that the artist has the major name recognition that many others writing about China lack. “People will be reading it not because he’s Chinese and not because the book is about China. They’ll be reading it because they’re interested in art and they’re interested in Ai Weiwei.”

Similarly, while Hessler’s books are often considered the gold standard among China watchers, Lusby notes that they are often read as travelogues rather than China books.

Hessler says that publishers were less convinced there was a wide readership for books on China when his first book, River Town, the original hardback of which features a yellow image of terraced hills along the Yangtze River, was picked up by a publisher in 1999. And Hessler himself wanted the cover to capture the importance of the particular countryside landscape he was writing about.

However, things had changed by the time Hessler was preparing his 2006 book Oracle Bones for publication, and he asked that his books not have red jackets to avoid the red China book cliche.

“I also just don’t much like the color red…and I also didn’t want the title to have ‘red’ in it,” laughs Hessler.

While red jackets have been the subject of a “long, long running chuckle among China watchers,” Ash says that writers often don’t have the final say when it comes to their book’s cover design or even the title. “In the end, it’s their [publisher’s] money and their call on what goes on the cover.”

But Lusby is more optimistic and offers some advice for writers hoping to publish a book on China.

“I would always tell them to go into the Bookworm [the now-shuttered iconic independent bookstore in Beijing] because that was the bookshop library that had the biggest selection of China titles available in China in English. I would tell them to go and stand in front of their China interest shelf and tell me what color they see, and then tell me what color they therefore think would stand out as a China book, and maybe go in that direction.”