China to limit the export of two critical metals used in chips

Beijing will impose export restrictions on gallium and germanium, two key metals needed to manufacture semiconductors and other electronics, and which are primarily sourced from China. The move has raised concern over an intensifying global battle on the supply of key chipmaking technologies.

China will impose export restrictions on two key metals that are used in the production of semiconductors and other electronics, China’s commerce ministry announced in a statement (in Chinese) on July 3. The restrictions will come into effect on August 1.

“In order to safeguard national security and interests, with the approval of the State Council, it is decided to implement export controls on items related to gallium and germanium,” China’s Ministry of Commerce (MOFCOM) and the General Administration of Customs (GAC) said in a notice.

According to the notice, the ministries listed eight items related to gallium and six items related to germanium. Producers will need to apply for a license from China’s commerce ministry and will be required to report details of the overseas buyers and their applications in order to ship the metals overseas.

“China is always committed to keeping the global industrial and supply chains secure and stable, and has always implemented fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory export control measures,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Máo Níng 毛宁 said on July 4 of to the export restrictions. “The Chinese government’s export control on relevant items in accordance with law is a common international practice, and it does not target any specific country.”

South Korea’s commerce ministry convened an emergency meeting to discuss China’s decision. “We can’t rule out the possibility of the measure being expanded to other items,” said Joo Young-joon, South Korea’s deputy commerce minister.

Meanwhile, Japanese trade minister Yasutoshi Nishimura said Tokyo will follow how Beijing will implement the rules on the two metals, while studying the impact on Japanese companies. “If any measures are unfair toward Japan in light of international rules such as those under the [World Trade Organization], we will act accordingly,” Nishimura said.

China does the lion’s share of gallium and germanium production

China is the leading producer of many critical raw materials in global mining, with 90% of the world’s rare earth production capacity. While data on the trade flows of small and niche markets are difficult to obtain, China remains the top global source for the two metals, with about 94% of the supply of raw gallium and 83% of germanium production, according to a 2023 study on critical raw materials by the European Union (EU).

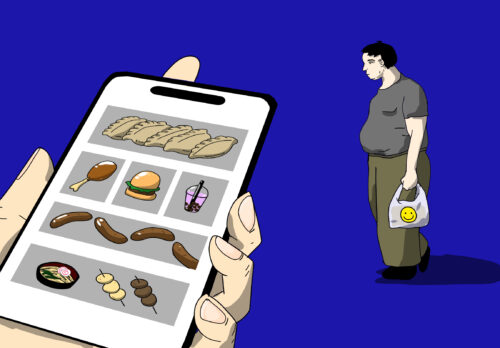

The two silvery metals are involved in specialized uses in chipmaking, as well as in equipment for communications and defense. Gallium is used in the production of compound semiconductors, which power everything from mobile phones, 5G networks, solar panels, to military hardware. The use of germanium, on the other hand, includes fiber and infrared optics, night-vision goggles, PET plastics, and space exploration. Most satellites are powered with germanium-based solar cells.

Both metals have been listed on the 2022 U.S. Critical Minerals List and the 2023 EU List of Strategic Raw Materials as minerals that are essential to their economic and national security. According to January 2023 data from the U.S. Geological Survey, the U.S. imported more than half of its supplies of gallium and germanium from China between 2018 to 2021, with 53% of gallium and 54% of germanium. No domestic primary gallium has been recovered since 1987 in the U.S., while zinc concentrates containing germanium were produced at mines in Alaska and Tennessee in 2022.

“In some sense, [China’s] actions are what pundits have been talking and worrying about for the last couple of years. These two minerals are byproducts of zinc mines, so starting domestic production [in the U.S.] is complicated,” Ian Lange, director of the Mineral and Energy Economics program at the Colorado School of Mines and faculty fellow at the Payne Institute, told The China Project today. “There are zinc mine tailings as well as potential zinc deposits in the U.S. However, permitting and setting up processing facilities takes time.”

“As byproducts, their quantities are small, and thus it is difficult to see a mine and processing facility funded through only sales of gallium and germanium. This is a difficult aspect of building a domestic mining supply chain,” Lange added.

The EU, on the other hand, imports 27% of its gallium and 17% of its germanium from China, according to a 2020 European Commission report (PDF download here). EU demand for gallium is expected to grow 17-fold by 2050.

Growing global red tape on critical minerals

China’s most recent rules on gallium and germanium come as part of a growing number of export restrictions enacted by various countries on critical minerals, according to an OECD report published in April that warned of its potential threats to undermine global efforts for a green energy transition.

Beijing has increased the number of restrictions on critical raw materials needed for electric cars and renewable energy, such as lithium, cobalt, and manganese by a factor of nine in the 11 years to 2020. India, Argentina, Russia, Vietnam, and Kazakhstan are the other five of the top six countries in terms of the number of new export restrictions.

“Some of these countries also account for the highest shares of critical raw material import dependencies of OECD countries,” the report stated. “In other words, OECD countries have been increasingly exposed to the use of export restrictions for critical raw materials.”

Meanwhile, the production of critical raw materials is becoming more concentrated among the top producers, including China, Russia, Australia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe.

“The research so far suggests that export restrictions may be playing a non-trivial role in international markets for critical raw materials, affecting availability and prices of these materials,” the report added.

Tit-for-tat technology curbs?

While China’s Foreign Ministry denied that the metals controls are meant to target any one country, the restrictions come amid an intensifying global battle to control key technologies used to make hardware such as semiconductors and solar panels.

On June 30, the Netherlands announced another set of controls that will limit the sale of high-end semiconductor equipment abroad, expanding on U.S.-led efforts to curb China’s chipmaking industry. The Hague’s move, set to come into force on September 1, will require dozens of Dutch firms — including ASML, one of the world’s most important producers of semiconductor machinery — to apply for an export license to supply certain advanced semiconductor manufacturing technologies overseas.

The U.S. is also reportedly considering tougher curbs on AI chip exports to China as early as next month, the Wall Street Journal first reported on June 27. The curbs would make it harder for Nvidia, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD), and other U.S. chipmakers to sell their chips to customers in China and other countries of concern without first obtaining a license. It is part of the final set of rules that will expand on the Biden administration’s sweeping export control restrictions announced in October 2022, aimed at “restricting the [People’s Republic of China’s] ability to obtain advanced computing chips, develop and maintain supercomputers, and manufacture advanced semiconductors.”